100th Anniversary of the Chinese Exclusion Act

Chinese Canadians have long been victims of discrimination, despite their major contributions to the development of their adopted country.

June 26, 2023

THE CHINESE IMMIGRATION ACT

Passed on June 30, 1923, the Chinese Immigration Act—also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act—became law on July 1, Dominion Day, which the Chinese Canadian community referred to as “Humiliation Day.” The Act marked the second phase of the government’s racist anti-Chinese policy. The first such federal law was adopted in 1885 in the form of a head tax ($50) imposed on every Chinese person seeking entry into Canada. This tax was raised to $100 in 1900 and to $500 in 1903 (equivalent to nearly two years’ salary).

In effect from 1923 to 1947, the federal government’s Chinese Exclusion Act stipulated, “No person of Chinese origin or descent […] shall be permitted to enter or land in Canada.” The only categories of immigrants allowed to enter (only fifty or so people were admitted in two decades) were members of the diplomatic corps, consuls, children born in Canada, merchants, and students.

| Discover the exhibition Swallowing Mountains by the multidisciplinary artist Karen Tam |

Among the prohibited classes were the following: “Idiots, epileptics, etc., diseased persons, criminals, prostitutes and pimps, procurers, beggars and vagrants, alcohol or drug addicts, mentally or physically defective, advocates of force or violence against organized government, members of unlawful organizations, conspirators, illiterates, deported persons.”

IMPACT ON CHINESE CANADIANS

This discriminatory, xenophobic law violated human rights and was an example of institutionalized racism. The exorbitant head tax imposed by the 1885 federal act meant that, from 1885 to 1923, generally only Chinese men could immigrate to Canada. The majority of them helped construct the Canadian Pacific Railway’s transcontinental railroad, hoping to earn enough money to bring their families over. The 1923 law squashed these plans and destroyed their chances of being reunited with their families on Canadian soil. It also had a tremendous impact on the Chinese community, resulting in a disproportionately high number of men and the creation of what were known as “bachelor societies.”

The law kept families apart for decades or sometimes forever. Only in 1967, 20 years after the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act and notably due to pressure from Chinese Canadians who had served the country in the Second World War, did Canada truly open its borders to the Chinese. The government overhauled its Immigration Regulations and established new standards for evaluating immigration candidates. At that point, more Chinese citizens met the criteria for admissibility, which created a fairer immigration process and consequently increased access to Canada.

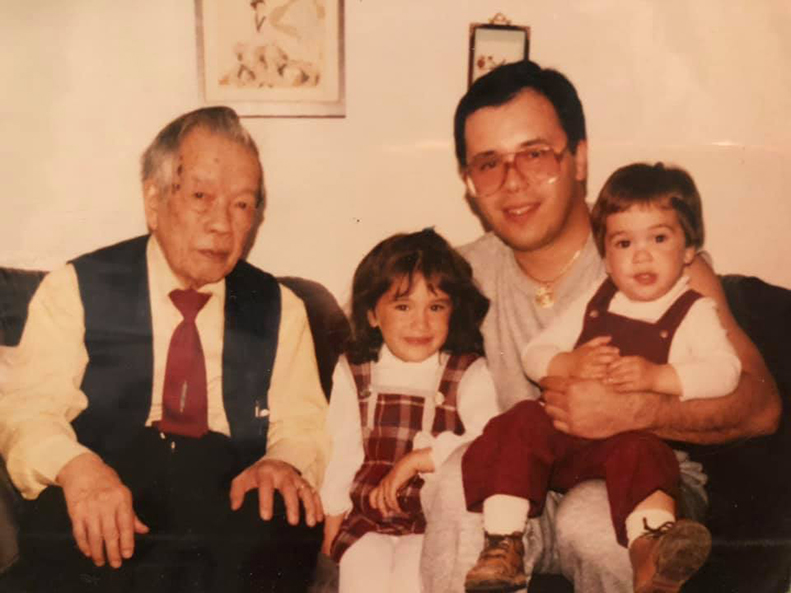

Forced to live far from their loved ones, an entire generation of men was scarred by melancholy, solitude and distress, while back in China, many women and children, suffering from the absence of a husband and father, starved to death as they were unable to support themselves. Arriving in Canada in early 1920, my paternal grandfather, Georges Lin Jew Cha, lived through this dark period, unable to bring his wife and son from China.

My father, Philippe Joseph Kuo Doon Cha, the product of a second marriage with a French-Canadian, was born as a direct consequence of this law. My grandfather did not reunite with his first family until decades later, an event with its share of turmoil and challenges, as you can well imagine. In fact, my father only learned of the first family’s arrival in Montreal several years after it happened.

CANADIAN GOVERNMENT'S OFFICIAL ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Many Montrealers of Chinese origin, like my father, are in fact commonly known as “half-Chinese.” Like others in his position, he shares the distinct features of people whose identity has been shaped by two cultures. It was not until the early 2000s that the government officially acknowledged the harmful effects of the law. On June 22, 2006, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper offered a full apology to Chinese Canadians for the Head Tax and expressed his deepest sorrow for the Chinese Immigration Act, which he described as a grave injustice.

On May 30, 2023, the Government of Canada recognized the national historic significance of the Exclusion of Chinese Immigrants. The Honourable Steven Guilbeault, Minister of Environment and Climate Change and Minister responsible for Parks Canada declared: “This land, now known as Canada, was and continues to be shaped by the contributions of immigrants and Indigenous peoples alike. The designation of the Exclusion of Chinese Immigrants as a national historic event, 100 years since its enactment, acknowledges the tragic injustice that Chinese Canadians suffered, while also offering an opportunity to reflect on the importance of combatting anti-Asian racism. The Government of Canada is committed to ensuring that we have opportunities to learn about the full scope of our shared history, including the tragic and shameful periods that are part of our collective past.”

Like many other Montrealers of Chinese descent, I share this heritage and this duty to remember, as do all citizens of the city and the country.