Researching the history of wampum belts

The challenges of trying to retrace the provenance and history of the Museum's wampum belts.

January 17, 2024

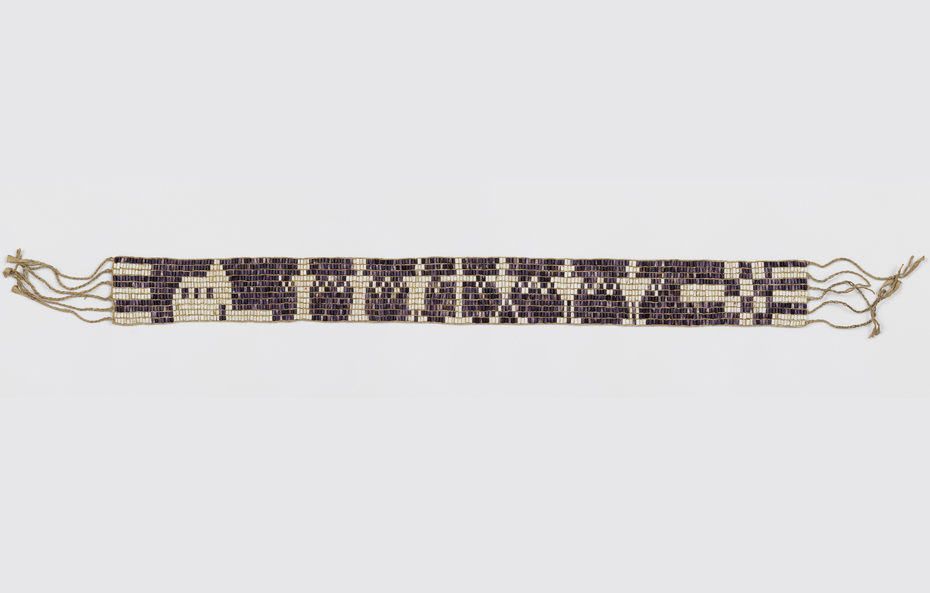

In 2022, I had the privilege of being hired by the McCord Stewart Museum for a specific assignment: do my best to trace the provenance of the wampum belts in the Museum’s collection for the exhibition Wampum: Beads of Diplomacy.

Many of these objects were kept by the Indigenous communities who originally received them, and some wampum belts are still found in these communities. However, in the early 20th century, some were sold off to private collectors and non-Indigenous institutions. David Ross McCord (1844-1930) was among the collectors who actively sought to purchase wampum belts.

Some of this research had already been carried out by Jonathan Lainey, Curator, Indigenous Cultures, at the Museum. He traced the provenance of two wampum belts in the Museum’s collection, establishing that the “Two Dog Wampum” came from Kanehsatà:ke and that the wampum belt with accession number M20401 came from Wendake. I hoped to obtain similarly conclusive, or at least satisfactory, results for the other wampum belts, but my efforts were stymied by a man named David Swan.

Methodology and reality

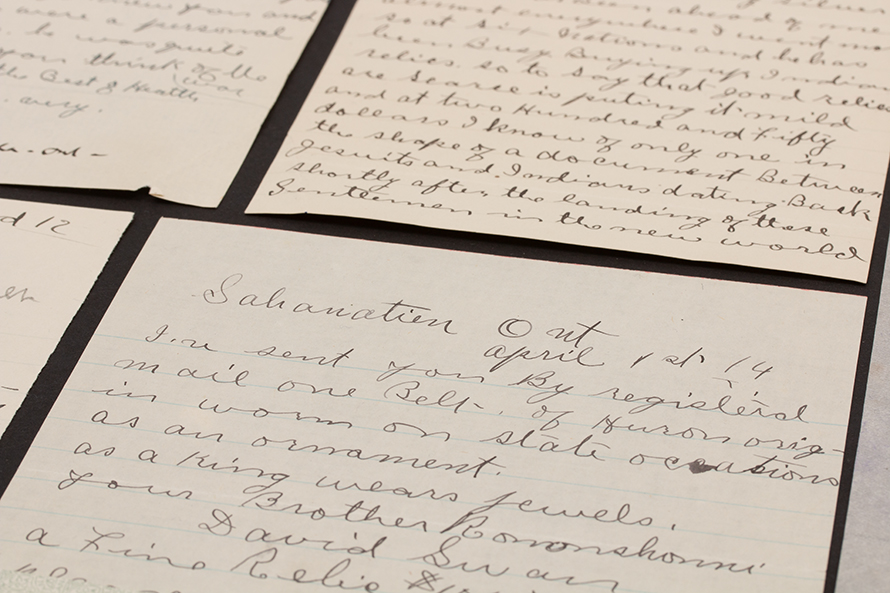

To determine the provenance of the Museum’s wampum belts, I began reading David Ross McCord’s correspondence, from which the excerpts in this article were taken.

| See the McCord Family Fonds on the Online Collections platform |

Other than the fact that it was sometimes very difficult to decipher the handwriting of certain correspondents, I ran into two main problems during my research. Firstly, the letters sent and received by McCord offered little or no information on the provenance of the wampum belts and, secondly, the few clues provided had to be taken with a grain of salt as ‘facts’ were sometimes wrong. For example, in his work on the “Two-Dog Wampum,” Lainey showed that the provenance indicated by David Swan, the man who sold the belt to McCord, was incorrect.

David Swan: A laconic intermediary

Who was David Swan? According to the letters in the Museum’s possession, Swan supplied McCord with over half of the wampum belts and various Indigenous objects in his collection. However, very little is known about him, other than he was born in Kanehsatà:ke, called himself “a direct descent of the famous Iroquois warriors,” and was the brother of Chief Joseph (Sò:se) Swan Onasakenrat.

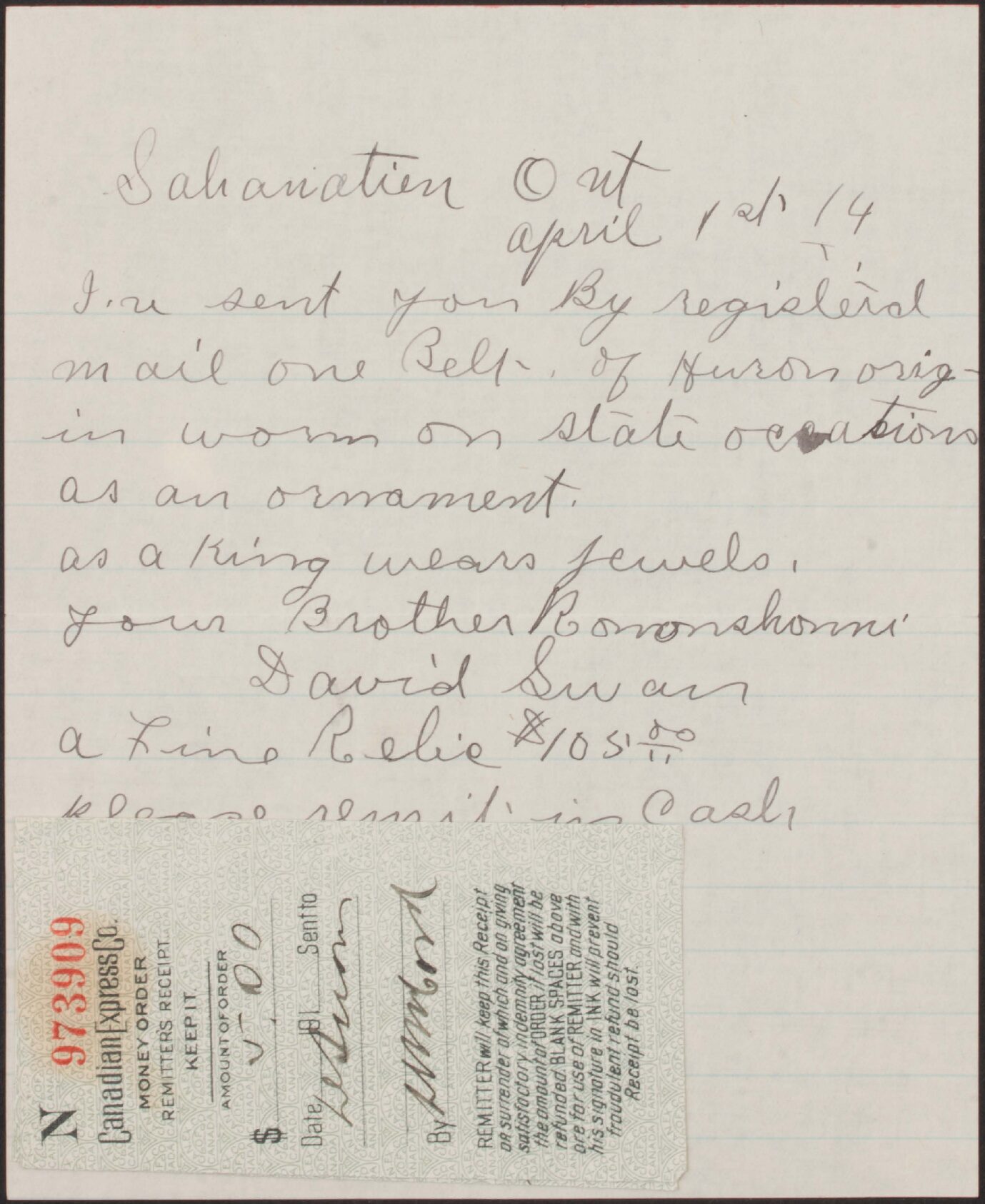

Swan appears to have been living in Bala, Ontario, in 1908, which is when he made contact with McCord. According to his letters, however, he travelled to numerous Indigenous communities throughout the Great Lakes region, all the way to the outskirts of Montreal, looking for items to offer the collector. Swan’s letters were sent from locations like Ruel, Byng Inlet, Moraviantown, Sahanatien, Parry Island, Kahnawà:ke and Kanehsatà:ke.

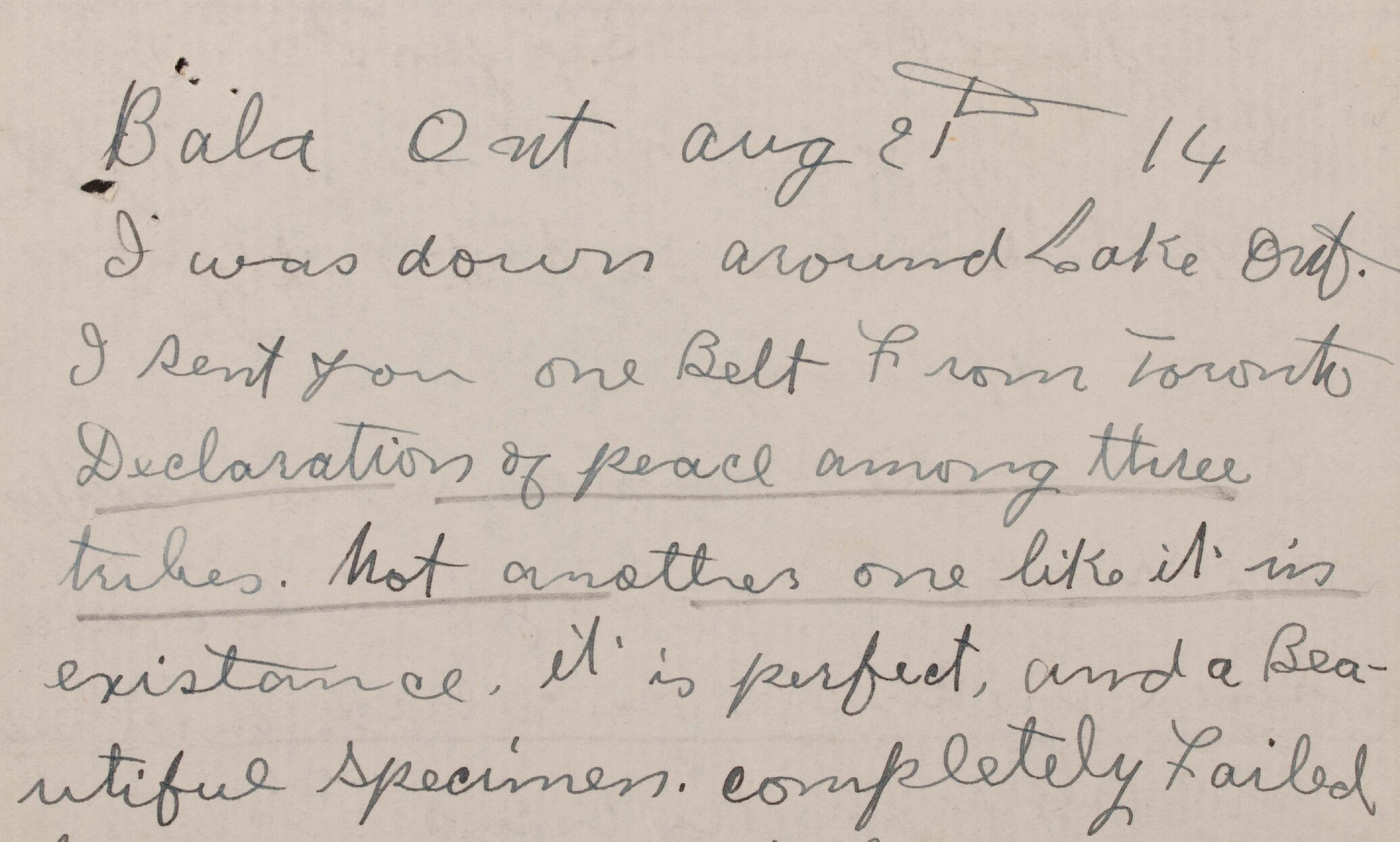

Swan provided few details about the provenance of the objects he acquired. From his home in Bala, he wrote to McCord, ”I have sent you a belt price $75.00,” offering no information on the provenance or identity of the wampum belt in question. In another letter, he was similarly vague, “ I was down around Lake Ont. I sent you one belt from Toronto Declaration of peace among three tribes.” Fortunately, in the latter case, it was possible to identify the wampum belt in question thanks to a handwritten document in which McCord describes some of his wampum belts by linking them to Swan’s letters, although the exact provenance remains unknown.

Reinventing the history of wampum belts

As a good salesman, Swan would describe his wares in terms that highlighted their uniqueness: “One belt of Huron origin worn on state occations [sic] as an ornament as a king wears jewels” and “Not another one like it in existance [sic].”

He also did not hesitate to interpret the importance of wampum belts to increase their value, like his letter about the wampum belt with accession number M1905. This belt, which Swan said came from Georgian Bay or Lake Huron, features a church and six human figures separated by a cross.

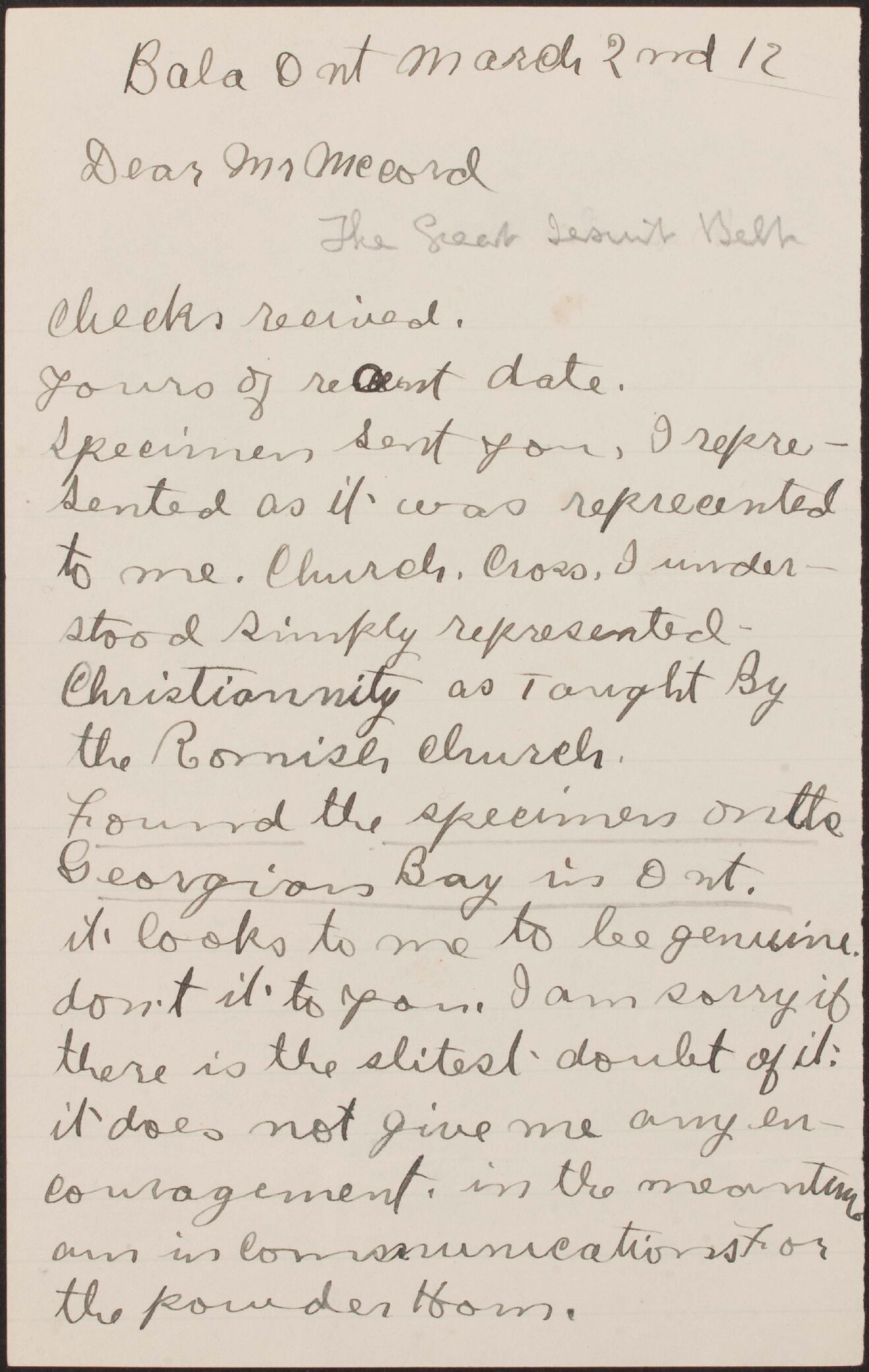

In his first letter to McCord, Swan wrote, “one in the shape of a document Between Jesuits and Indians dating back shortly after the landing of these gentlemen in the new world […].” He then noted that the Indigenous people were “Hurons” and, in another letter, he mentioned the presence of nuns alongside a priest. Finally, over a month later, Swan recounted how “The Great Jesuit Belt” was actually described to him: “I represented [it] as it was represented to me. Church. Cross. I understood simply represented Christiannity [sic] as taught by the Romish church.”

In addition to these bits of information, McCord added that the wampum belt represents the first church of Ossossané (1638) as well as two Jesuit priests and one lay brother. He later wrote that one of the priests was the Jesuit Jean de Brébeuf. Finally, a registry held by the Museum includes a note that the second Jesuit was Father Jérôme Lallemant. This is a far cry from the brief description “Church. Cross” that Swan was given by the wampum belt’s original owner.

The collectors' market

Why wasn’t Swan more specific when discussing the provenance and history of wampum belts? The most likely hypothesis is that he did not want to jeopardize his role as McCord’s preferred purveyor of objects.

According to the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator, the price of the wampum belts Swan sold McCord varied from $650 to $6,500, in today’s dollars. Obviously, Swan did not indicate his share of the profit on each sale, but one can assume that his business was relatively lucrative, given that he would travel hundreds of kilometres to close deals. Of course, he made even more money when he took wampum belts without permission or “borrowed” them without ever bringing them back, a regular occurrence in the process of collecting Indigenous objects.

Swan was not the only dealer to take items from Indigenous communities in this way. He mentions an “American with the Big silver dollar” who was one step ahead of him.

This search for Indigenous objects took place in a particular context. As Lainey explains, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Indian Act was being actively enforced. Faced with challenging socio-economic conditions, some Indigenous people decided to sell their community’s objects, to the benefit of interested collectors, some of whom thought that Indigenous cultures were doomed to extinction.

Nearly all the collectors were men. Although some women encouraged McCord’s activities, like Mabel Molson who gave him $2,000 to purchase medals, the only woman’s name mentioned in connection with the wampum belts was a widow, Mrs. David Denne. McCord wrote to her in 1919, hoping to get the wampum belt that had belonged to her late husband. “You have a small wampum belt. I would like very much if you would honour me by placing it in this National Museum in memory of him.”

The widow granted McCord’s request a number of years later, in 1930.

Although I did not succeed in retracing the exact provenance of the wampum belts in the Museum’s collection, my research did shed light on the circumstances surrounding the movement of these objects.

References

Lainey, Jonathan, “Wampum in Quebec from the 19th Century to the Present Day: Appropriation, Loss, Identification,” Gradhiva, 33, 2022, p. 98-117. Published for the exhibition Wampum. Perles de la diplomatie en Nouvelle-France, Musée du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac, Paris.

Lainey, Jonathan, (with Anne Whitelaw) “The Wampum and the Print: Objects Tied to Nicolas Vincent Tsawenhohi’s London Visit, 1824–1825,” in Beverly Lemire, Laura Peers, and Anne Whitelaw (eds.), Object Lives and Global Histories in Northern North America: Material Culture in Motion, c. 1780-1980. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021, p. 176-202.

Lainey, Jonathan, “Les colliers de wampum comme support mémoriel : le cas du Two-Dog Wampum,” in Alain Beaulieu, Stéphan Gervais and Martin Papillon (eds.), Les Autochtones et le Québec. Des premiers contacts au Plan Nord. Montreal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2013, p. 93-112.

Franco, Marie-Charlotte, La décolonisation et l’autochtonisation au Musée McCord (1992-2019), PhD thesis (Museology), UQAM , 2020, https://archipel.uqam.ca/14519/1/D3823.pdf