Fashion And Montreal’s Winter Carnival

Was there a Winter Carnival “look?” What was everyone wearing on the giant toboggan slide?

February 8, 2023

This tailor-made dress looks a lot like the fashions illustrated in magazines from 1887, but during one particular mid-winter week in Montreal, it may have appealed to tourists as a fashionable indoor adaptation of the outdoor clothing seen everywhere in the city’s streets and parks.

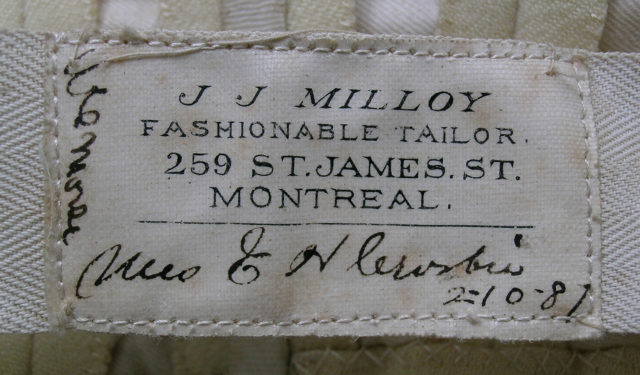

In February 1887, Medora Robbins Crosby of Boston, Massachusetts, bought this dress by fashionable tailor J.J. Milloy, located at 259 St. James Street in Montreal. Her husband, Edward Harold Crosby, was a journalist with the Boston Post on assignment in the city. They had come to take in the Winter Carnival, along with many other American tourists.

| Discover the first part of the story J. J. Milloy: A Fashionable Montreal Tailor of a Century Ago |

Medora may well have heard of Milloy’s establishment before she arrived in Montreal. Savvy American shoppers knew that Canadian tailor-made woollen clothing offered better quality at much lower prices than they could get at home. Many Montreal merchants promoted their wares for this special occasion, and Milloy was known to do a brisk business with the out-of-town clientele during Winter Carnival.

FASHION INSPIRATION IN 1887

This model would likely have been on view at the shop that week for customers who wanted to have it made to measure for them. But what might have inspired Milloy’s design choices? And what might have drawn Medora to this white dress with its bright red trim?

The silhouette with a large bustle, and the use of fabric in contrasting colours to create a horizontal striped effect on the skirt were the height of fashion in 1887, as evidenced by illustrations from the period. Milloy might easily have designed the skirt and the epaulet trim on the bodice based on a fashion plate similar to this one from the London-based journal The Queen.

FASHION FOR WINTER SPORTS

For the colour scheme and trim placement, he might also have had in mind the garment that was the sartorial signature of the week’s event. In the city’s colourful show of winter sports, Medora would have found herself immersed in a sea of snowshoers and tobogganers in blanket coats.

Before she even arrived, she would have seen them illustrated in white with red trim on the cover of the program sold by the Central Vermont Railroad. An illustration of the feminized version appeared on the souvenir program sold in Montreal as well.

Blanket coats featured prominently in store windows at dry goods and tailoring establishments. Some visitors to the city would go to Notman’s Studio to have their portraits taken in a blanket coat, as a souvenir of the carnival experience.

Most blanket coats were off-white with red- or blue-coloured epaulets and brightly coloured stripes at the hem and cuffs. While surviving examples of women’s coats from this period are rare, the Museum does have some in its collection, including this one from the 1880s, whose cut and striped pattern are very typical, in contrast with the unusual dark ground colour.

Might the design of the Milloy dress have perhaps been a clever visual play on the blanket coat? It is perhaps not similar enough to say with certainty, nor is it different enough to entirely discount. And if the dress intentionally referenced this coat style, what would that mean?

| What can a garment label tell us? Who Wore this Dress? |

AN INDIGENOUS IDENTIFIER

The blanket coat originated from a British-manufactured garment worn during the fur trade in the 17th and 18th centuries. Its widespread use among Indigenous peoples in the trade resulted in it becoming an Indigenous sartorial identifier.

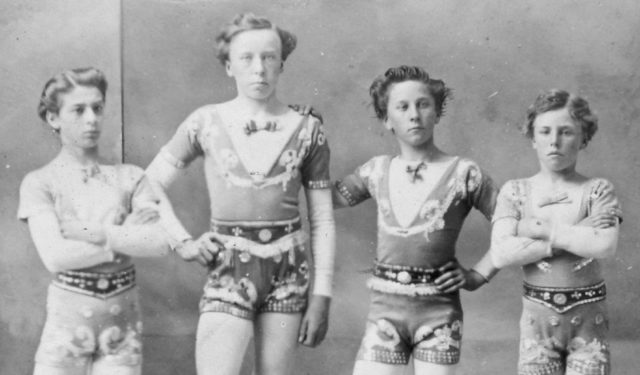

In the mid-19th century, after pushing back Indigenous peoples to the periphery of the land they once occupied, settlers adopted snowshoes and toboggans—both Indigenous inventions for travelling over North American terrain—and turned them into winter sports, overlaying them with the values of British fair play by forming clubs and organizing competitions. They also adopted the garment they associated with Indigeneity for these activities.

Tobogganing and snowshoeing became a colonial performance that naturalized settler dominance over Indigenous peoples. The very picturesqueness of the Montreal Winter Carnival was rooted in this performance of demonstrating settlers’ ability to conquer the hostile winter terrain by actually enjoying it.

In this context, blanket coats became imperial livery—garments that in a very banal and insidious way perpetuated celebratory narratives of nation-building. Nor was it the only instance of attire inspired by projects of imperial dominance.

FASHIONABLE ADAPTATIONS

There are similarities in the way sailor dress was also adopted into fashion. It, too, was inspired by a rough occupation that sustained an empire, albeit on different terrain. Its typical features were constantly reinvented and reinterpreted in fashion for women and children in the same period. In this mid-1880s example, it was reinterpreted in fashion in a way that also resembles the Milloy dress.

Intrinsic to the fashionable adaptations of both sailor dress and blanket coats is the act of remembering core myths of a glorified past. Milloy’s tailor-made dress may have looked a lot like the latest fashion plates, but I venture that in the particular context where its visual references would be readily grasped by a tourist surrounded by blanket-clad throngs in streets and parks, it was yet another iteration of that colonial performance.