Eating Local

Vegetable patches, community gardens, public markets: Rediscover city life of yesteryear and the access it offered to local farm produce.

April 16, 2025

Locally grown food has long been part of the urban experience. These photographs from the Museum’s collection, taken primarily in and around Montreal between the 1860s and the 1990s, illustrate a variety of settings – backyard vegetable patches, community gardens, public markets – where produce takes centre stage and fosters human connection.

As today’s city-dwellers become increasingly concerned with how food gets to their table, it bears remembering that in the past, access to local agricultural products was a normal part of city life.

The Saint-Sulpice Seminary, constructed between 1684 and 1687, is one of the oldest buildings on the island of Montreal. Some 335 years later, it is still a residence for Sulpician priests.

This view from one of the towers of Notre-Dame Basilica looks onto the seminary’s private monastic garden, which also dates back to the French Regime.

Created in the tradition of medieval cloister gardens, the geometric design and symmetrical walkways appear on a late 18th century plan of the city. Though the garden was used to grow produce, it also incorporated ornamental elements, making it a peaceful place for leisure and prayer.

This vegetable garden behind the Grey Nuns’ hospital was photographed in 1867. Notice the rows of glass-topped wooden boxes on the ground at the lower right? Each one a mini-greenhouse, they enabled produce to survive an early planting and thus extended Montreal’s short growing season.

Religious communities of the nineteenth century were known for their self-sufficiency. The Grey Nuns grew produce not only for their own members, but also for the residents of their hospital. Though relatively small, this garden nonetheless supplied the community with a portion of what it needed.

Most of the produce and grains consumed by the community and its hospital each year were grown in fertile farmland at the Seigneury of Châteauguay (located about 20 km southwest of Montreal), which had been purchased by Grey Nuns’ founder Marguerite d’Youville in 1765.

Bonsecours Market, a domed waterfront building constructed between 1844 and 1847, initially housed a public market on the ground floor along with meeting and exhibition rooms on the upper floors.

By 1904, Bonsecours Market was the main public market in Montreal. Its interior was primarily devoted to market stalls. Twice a week during busy times of year, particularly during the late summer and early fall harvest period, farmers and their parked vehicles would fill the neighbouring streets. Bonsecours Market was a central point of contact between Montreal shoppers and rural farmers.

The City of Montreal constructed the “New Market” at this site in about 1807, to relieve pressure on the old market at Place Royale, by then too crowded for the growing city.

By 1815, this marketplace featured a long wooden shed with overhanging eaves, protecting buyers and sellers from precipitation and sun. After nearby Bonsecours Market opened in 1847, the wooden hall was demolished. Renamed Jacques Cartier Square, the site became an “overflow” space for farmers on market days.

Wholesale and retail sales took place here. Henry Macey’s wagon, in the left foreground, may have just arrived. His horse is still hitched, unlike the vehicles of the vendors in the background with their empty shafts. Macey was likely purchasing produce for his grocery, located in the small neighbourhood of Victoria Town, near the Victoria Bridge.

Growing vegetables and fruit for the local market was an important source of income for Montreal-area and Canadians farmers in the early twentieth century.

Donald Ross, seen on the right, was a leading Edmonton market gardener and hotelier known for producing the largest, most bizarrely shaped and most diverse vegetables in the region. An enthusiastic participant in agricultural society competitions, Ross created a style of display that emphasized the visual appeal and abundance of his harvests.

Agriculture on Montreal Island dropped sharply after the Second World War, as suburban farmland was increasingly sold and subdivided for new housing developments.

According to contemporary accounts, the Montreal melon was similar to a large cantaloupe, but green-coloured, and with a slight nutmeg flavour. It was a popular export to restaurants and hotels in the United States and advertised in local newspapers from the late 1890s to the end of the 1930s.

Benny Farm was leased for market gardening when this photograph was taken, but during the previous century, it was the summer estate of the Benny family, who hired a farmer to manage the farm’s agricultural activity.

Robert Benny, a Montreal hardware merchant, seems to have taken a particular interest in farming. He entered local agricultural society competitions in the late nineteenth century, winning awards for his produce and grains, which included barley and wheat, carrots, turnips, and mangold wurzels, a type of beet often used as animal feed.

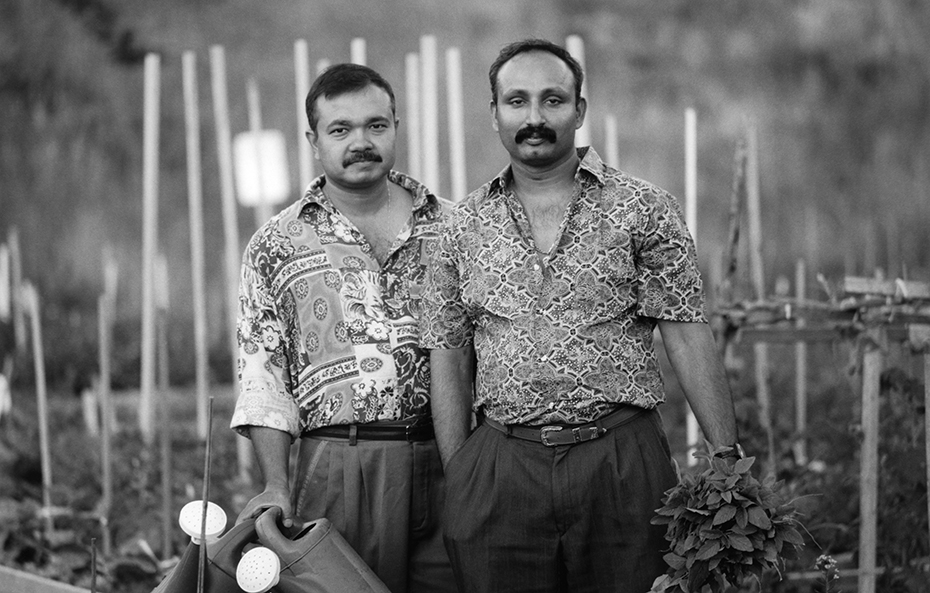

Ile Bizard is a small island off the western end of Montreal. It transitioned from subsistence farming in the nineteenth century to market gardening in the twentieth, replacing some of the farmland lost due to Montreal’s fast-growing suburbs.

In 1925 and 1926, Robert Bruce Bennet photographed a number of sunny, peaceful scenes on Ile Bizard, from rural roads, fields and old farmhouses, to a wayside cross and the current-powered ferry. Albert Chaurest, a farmer and market gardener, later the mayor of Ile Bizard, employed a hired man, along with his three sons Conrad, Lionel and Roch, and their cousin, to harvest and pack tomatoes for the Bonsecours Market in 1925.

Ile Bizard retains a great deal of its rural character even today, with a designated agricultural zone protected by legislation since the early 1970s.

By the 1930s and 40s, the advent of motorized vehicles made the market-day trip to Montreal much easier for farmers from nearby counties such as Terrebonne, Chambly, Two Mountains and Laval. Travel in a horse-drawn vehicle had been much more difficult. Not only did it take longer, weather conditions sometimes presented additional difficulties.

In summer, those with a greater distance to travel would begin their trip the day before and arrive in Montreal late at night, sleeping in their wagons to be ready early the next morning. Travelling at night meant that they and their horses did not have to suffer the heat of the sun.

One farmer, interviewed by a local newspaper in 1904, explained that they often stayed home on cold winter days: “In winter we nearly get frozen, our goods are sometimes spoiled and our horses catch cold and die.” As a result, some farm and dairy products were scarce in the market on cold winter days in the horse-drawn era.

Planting a Victory Garden was promoted as a patriotic activity during the Second World War. By growing food for their own consumption, families could participate in the war effort, cut down on family food costs and adopt a healthy diet.

The idea of “war gardens” dates back to the First World War, but the term “Victory Garden” seems to have emerged in the United States, appearing in Montreal newspapers by 1942.

Early in the war, the Canadian Government was reluctant to promote gardening by urban amateurs, fearful that their inexperience would cause them to waste precious seeds, which were in short supply. With the seed shortage over by 1943, the Department of Agriculture began actively encouraging new gardeners to produce “health-giving, vitamin-rich vegetables.”

The Atwater Market, situated near the Lachine Canal in St. Henri, cost one million dollars to complete, opening to the public on Saturday, April 15th, 1933. There was no special ceremony to mark the event, only the simultaneous closing of the market building it was constructed to replace, the old St. Antoine Market on St. James Street.

When the Atwater Market first opened, its ground floor held twenty-one stalls for vendors of fruits and vegetables, poultry and fish. Twenty butcher’s stalls were on the second storey. The third floor, which doubled as a public hall, provided space for 160 farmers to display their products. A further one hundred and fifty stalls were available outdoors for farmers’ trucks and carts.

Montreal established its community gardening program in 1975, but a number of earlier programs helped pave the way for gardens like Châteaufort.

A successful, though short-lived, community gardening program began in 1917, when the City of Montreal offered 75 acres of unimproved parkland in different areas of the city to the families of soldiers serving in the First World War, returned soldiers, and widows of soldiers. Under the auspices of local associations and clubs, including the Khaki League and the Montreal Gardener’s Club, over one thousand plots were distributed. Participants received seeds, tools and fertilizer, and were offered horticultural classes.

The Community Garden League of Greater Montreal, initially organized as a relief program during the Great Depression, distributed plots of vacant land to unemployed men and their families. The League also provided tools and seeds, enabling men to occupy their time while providing vegetables for their families.

Starting with just 500 plots in 1932, by the following year, the Community Garden League had nearly 2,000 plots under cultivation in various neighbourhoods on the island from Verdun to Ahuntsic. Montreal’s Parks and Playgrounds Association continued this successful program through the 1950s as a recreational activity.