Two Amazing Women of the McCord Museum

Mary Dudley Muir and Dorothy Warren two amazing women who helped establish and care for the Museum during its first few decades.

March 2, 2022

Dedicated, rigorous and detail-oriented; creative, innovative, and bold. These qualities include some of the core values held by McCord Museum employees and could be used to describe any number of the wonderful colleagues and volunteers that I am privileged to work with on a daily basis.

They also apply very well to two staff members who helped establish and care for the Museum during its first few decades at McGill University. Although these amazing women both held the job title of Assistant Curator, their differing roles and responsibilities within the fledgling institution extended far beyond what might be required of any one individual in the McCord Museum today!

Mary Dudley Muir: Assistant Curator and Project Manager…

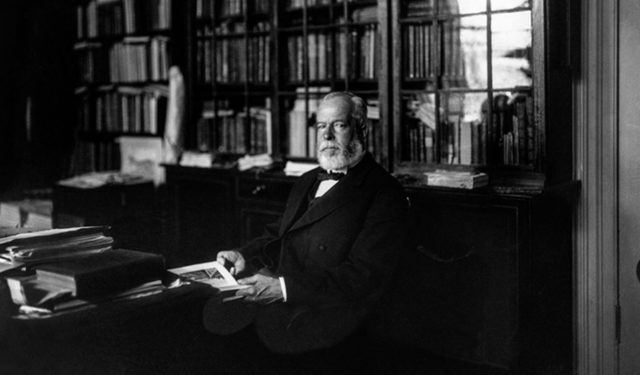

In 1920, David Ross McCord, the founder of the McCord Museum, described his assistant Mary Dudley Muir (1860-1936) as “one of the finest assets the University possesses.” Muir had previously been employed as a secretary at the Art Association of Montreal and was active in a number of cultural associations over the years.1 Miss Muir was, in David Ross McCord’s opinion, not only educated, with gracious manners, but “just the woman to aid in such work as this Museum” and “fitted to take my place after I am gone.”2 McCord’s trust in her was complete: as he wrote to Principal Sir Arthur Currie in 1920, “I have not and will not have a shadow of care—simply give her the keys.”

One of Muir’s first duties when hired in 1919 was to translate David Ross McCord’s vision of his National Museum into practice. This meant ensuring that the objects, along with carefully drafted labels, were located according to McCord’s planned geographical, thematic or temporal order, and properly displayed in cases, cabinets, and on walls in the various rooms of the Joseph House. In this sense, she was the Project Manager for the exhibition spaces when they first opened at McGill University.

This was not an easy task, if one is to judge by the notes on how the museum should be organized, scrawled in pencil by D. R. McCord in his distinctive and sometimes illegible handwriting. The surviving correspondence on the subject of the museum’s founding shows how very particular and exacting McCord was with regard to how his objects should be framed, displayed, and stored. Muir would certainly have needed to be a rigorous, dedicated, and very patient person!

However, Muir did have an opportunity to travel and learn from other institutions. In December 1920, The Gazette noted that, in addition to directing the process of making labels to accompany the objects, Muir was presently “in New York, in the course of visiting several of the principal cities of the United States for the purpose of getting in touch with the directors and curators of representative museum collections similar to that of the David McCord collection.”

Once the Museum opened to the public in 1921, Muir settled into a busy daily routine filled with administrative tasks. By 1922, she was no longer reporting to David Ross McCord, but to the McCord Museum Committee, which had taken on the role of Curator.3

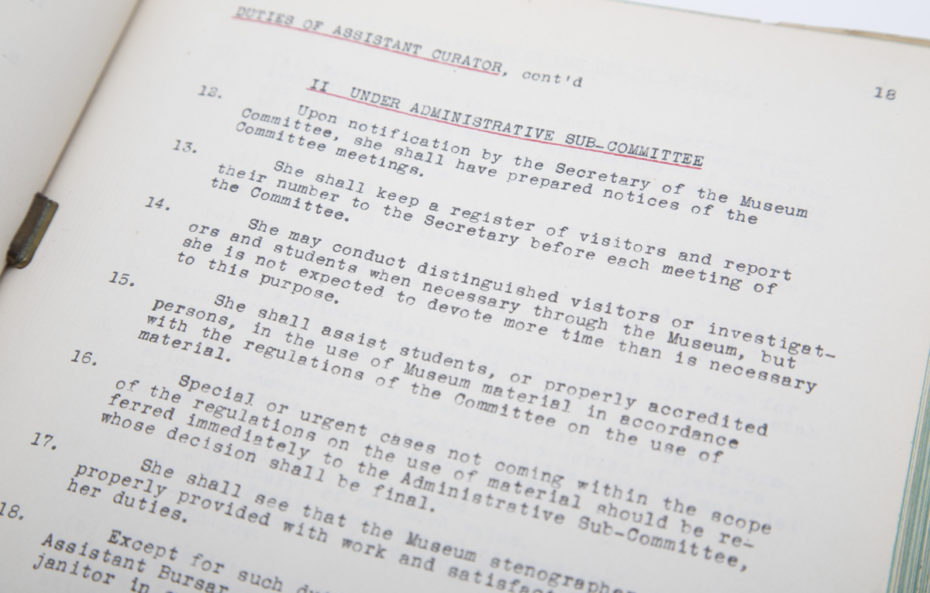

The Committee may not have trusted Miss Muir as implicitly as David Ross McCord had. In 1924, the Committee felt the need to draft a document setting out in minute detail the various duties expected of an Assistant Curator, including the preparation of potential donations or purchases for approval by the Committee, a task that involved obtaining “the best available information regarding the character, source and authenticity of material offered to the Committee for acceptance or purchase.” After the Committee met, it was essential that Muir “promptly acknowledge all gifts,” and return rejected material. Additionally, she was responsible for arranging the new objects in the exhibition areas, or placing them in “suitable storage.”4

…and office supply technician?

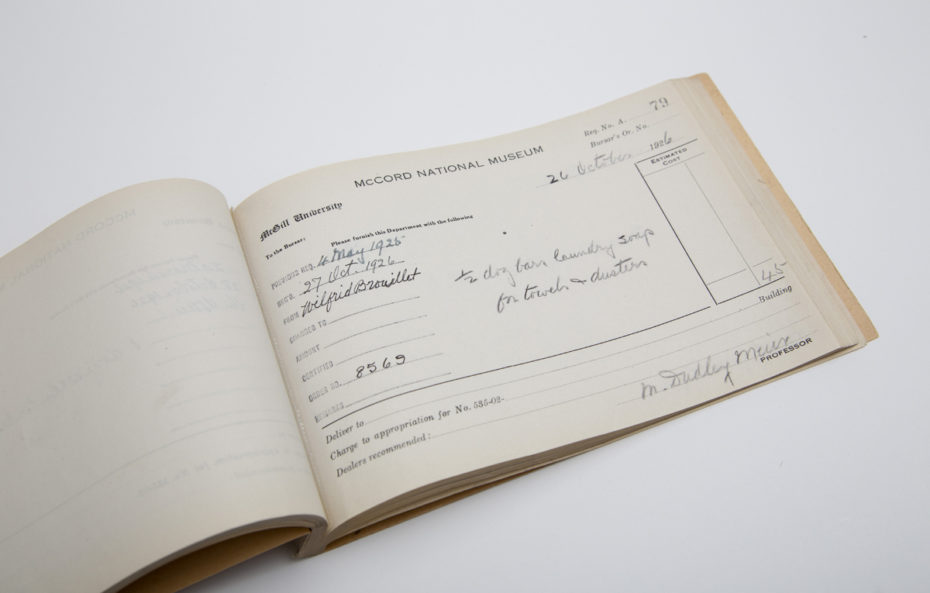

The Committee further required Muir to ensure that there were sufficient office supplies on hand in the store cupboard: enough to “prevent frequent mail re-orders,” but “not more than is necessary for the current Museum year.” Even the smallest of purchases needed authorization, but Muir seems to have accepted her myriad allotted duties and limited authority without complaint.

At least Mary Muir was given some autonomy: the Committee allowed her to “conduct distinguished visitors or investigators and students when necessary through the Museum.” However, she was “expected to devote no more time than is necessary to this purpose.” Presumably, they were worried that she would be distracted from the listing or “accessioning” of material, a task that, they noted, “must be regarded as her most important work.” The Committee also required her to notify them of any offers of assistance she received in identifying or classifying objects.

When Mary Dudley Muir became ill in May 1928, Dorothy Warren replaced her on a temporary basis. Upon Muir’s official retirement in January 1930, McGill appointed Warren as Assistant Curator.

Dorothy Warren: Assistant Curator (also actively involved in Exhibitions, Promotion, Communications, and Education)

Before her arrival at the Museum, Dorothy Perram Warren (1882-1957) had spent many years living in Italy and France with her husband, artist Frank Chickering Warren.

The picture that emerges from the McCord’s early institutional archives suggests that Dorothy Warren’s personality and skills were a good fit for the needs of the Museum at that time. She appears to have been a bold, energetic and creative person with many innovative ideas about promoting the McCord Museum in the public eye. During the summer of 1928, just after she became the Acting Assistant Curator, the number of visitors to the museum increased. The Committee noted this, thanking Warren for her efforts “in directing the attention of hotel visitors in Montreal to the McCord Museum.”5 In November, the Committee authorized her to have a Museum poster printed up for hotels, McGill buildings, and other locations.

Drawing crowds with temporary exhibitions

The number of temporary exhibitions also increased after Warren arrived. Mary Dudley Muir had been involved in a small number of special displays, most notably one in 1926 of material purchased from the family of Harry Hewitt Baines and another on James Wolfe in 1927. Exceptionally, both exhibitions were open to the public on Sunday afternoons, drawing crowds of visitors who could not normally visit the museum during its usual weekday afternoon opening hours. These exhibitions set a precedent, demonstrating a demand to which Mrs. Warren was ready to respond.

Beginning in March 1929, the McCord Museum opened on Sundays with a series of special exhibits, rotated weekly, ranging from themed displays of household objects from the French Regime, to baskets from North and South America. Volunteers from the History Association of Montreal helped show the public through the museum. The popularity of the special Sunday openings (654 people in two hours was the record)6 led the Committee to make a permanent change to the Museum’s hours.

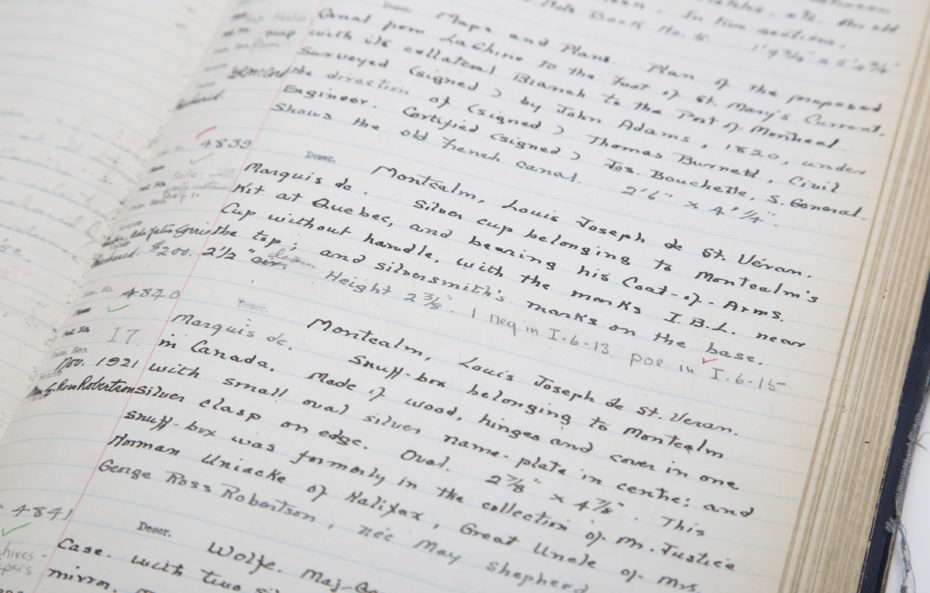

As was the case with Mary Dudley Muir, the Committee considered that the “most important and immediate” part of Warren’s work was accessioning objects.7 She pursued this directive energetically, managing the accession of about 3,000 objects per year between 1928 and 1931.8

Dorothy Warren was proactive in communicating historical information and promoting the McCord’s collections through various media, whether it was giving a speech over the radio extolling the importance of conserving historical documents, or delivering talks to local community groups. She even co-authored a short paper on a series of letters written by physician and judge Adam Mabane, which was published in the Canadian Historical Association’s report in 1930.9

Warren also demonstrated diligence with regard to the conservation of the objects under her care, reporting to the Committee in 1930 that the Wolfe letters and documents ought to be “put in drawers during the summer months” to be shown only on demand, in order to shield them from the strong light at that time of year. She later proposed and installed a special curtain to protect the documents from fading.

Arguably, Dorothy Warren’s most ambitious project at the McCord, executed with the help of her assistant Isabel Craig, a graduate student in History at McGill, was to develop a series of chronological exhibitions illustrating periods in Canadian history for groups of schoolchildren. These exhibitions were planned to coincide with the curriculum taught in local schools.

Warren and Craig prepared the exhibits and conducted most of the tours, giving visitors a short historical lecture. Though both were English speakers, they also arranged to offer a tour in French at 3 pm on Thursdays. It was not necessarily Warren’s idea to plan exhibitions specifically to educate schoolchildren, but she certainly seems to have brought the project to fruition with great success.

The closure of the McCord Museum in 1936, due to McGill’s financial difficulties during the Depression, meant Warren’s forced retirement from her position. It was by no means the end of her career, though. Newspaper articles report that she worked as a librarian for a number of years afterwards. In 1942, she helped plan a special “Canadiana exhibit” at the Montreal Children’s Library, using historical material borrowed from the McCord Museum. Of course, having been the Assistant Curator at the McCord Museum for eight years, she had no trouble identifying exactly which material she wished to exhibit!

NOTES

- Gazette (Montreal), “Miss M. D. Muir Dies,” Monday, November 2, 1936, p. 7.

- David Ross McCord to McGill University Principal Sir Arthur Currie, August 9, 1920.

- The initial deed of gift to McGill had stipulated that David Ross McCord retain the official title of Curator during his lifetime. However, McCord suffered from arteriosclerosis in his later years, which led to mental illness. Institutionalized at the Protestant Hospital for the Insane in 1922 and later transferred to the Homewood Sanitarium in Guelph, Ontario, McCord was no longer capable of participating in the day-to-day affairs of the Museum.

- Duties of Assistant Curator, Minutes of the McCord Museum Committee, December 1924.

- Minutes of the Committee, October 4, 1928.

- On May 23, 1929, The Gazette reported that on the previous Sunday, a record number of people (654) had visited during the two hours the Museum was open.

- McCord National Museum Memorandum of the meeting of the Administrative Sub-Committee, November 5, 1928.

- In comparison, a total of 5916 objects had been accessioned in the seven years prior to Dorothy Warren’s arrival. Report of the McCord National Museum Sept 1, 1930-Sept 1, 1931. P001, folder 7627.

- Mr. E. Fabre Surveyer, F. R. S. C. and Dorothy Warren, “Some letters of Mabane to Riedesel (1781-1783),” in Report of the Annual Meeting, Canadian Historical Association, Vol. 9, No. 1, 1930, pp 81-82.