The Irresistible Allure of Taxidermy

Taxidermied animals are a tasty treat for certain insects. How conservators prevent insect damage.

July 13, 2021

Taxidermied birds have a dynamic presence in our current artist-in-residence exhibition, Meryl McMaster – There Once Was a Song. Three objects from our collection form a series of Victorian still lifes incorporating preserved birds in naturalistic poses—two arranged under large bell jars and the third mounted in a fire screen. These tableaux complement a crow and a starling—two components the artist has incorporated into her multimedia installations.

A FASHION FOR EXOTIC BIRDS

Taxidermy in its earliest forms originated in the 16th century, and by the 19th century—the period from which the McCord objects date—techniques had improved significantly and its popularity had increased. Objects similar to these could be found in both museums of natural history and domestic household interiors. The acquisition and collection of exotic birds had become fashionable, their beauty and rarity made further desirable by their colourful and iridescent plumage.

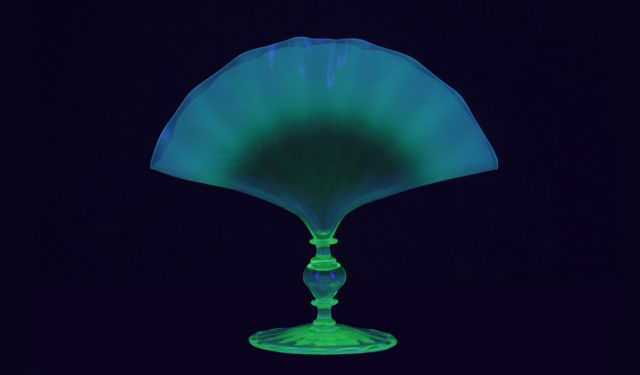

Among the most striking objects in the exhibition is a Victorian summer screen, originally used to hide or decorate an inactive fireplace during the warmer summer months.

The screen consists of an upright wooden frame supporting a cabinet with glass panels on the front and back and displays a series of jewel-toned birds, butterflies, and other insects posed on artificial twigs embellished with dried ferns and flowers. Because the screen sits on four feet, it was referred to as a cheval, or horse screen.

A FEAST FOR INSECTS

Insects pose a threat to the preservation of this type of object. While we find their plumage visually alluring, the feathers and skin can prove irresistible to some voracious insects.

From the earliest days of taxidermy, attempts at preserving birds, while also preventing such infestation employed several techniques. Birds were placed in glass jars or wooden barrels filled with brandy, or embalmed with aromatic spices or a drying agent such as alum or lime. Later methods involved placing the prepared skins in a warm oven.

Although these methods prevented the flesh from rotting, they did nothing to deter insects, and unfortunately caused other problems. The alcohol damaged the feathers, salt and alum hastened the disintegration of the specimen, and the exposure to heat caused deterioration of the feathers.

Further attempts at preserving the skins involved the application of a varnish containing a mixture of raw turpentine, camphor, and spirit of turpentine or a dry compound made from mercuric chloride, saltpetre, alum, sulphur, musk, pepper and ground tobacco. While these mixtures preserved the skin, they remained prone to insect damage.

FROM ARSENIC TO FREEZING

It was not until the late 18th century that apothecary and naturalist Jean-Baptiste Bécoeur formulated a secret recipe that, after his death, was revealed to contain arsenic. The mixture was highly successful in mitigating insect infestation, and was adopted as the standard treatment for taxidermied skins from this point forward, although its toxicity prevented it from being used exclusively, and some taxidermists chose to forego its use (Farber, 553).

The possibility of insect infestation through objects entering our collections has necessitated a policy of prevention, requiring the placement of most incoming objects into a large commercial freezer. The sustained low temperatures eradicate all stages of the insect life cycle: adults, larvae and eggs.

As the artist’s birds were not isolated in a display but were exhibited in the open, they posed a risk if insects were present. As a precaution, the preserved crow and starling spent a week in our freezer before their display. While freezing can be an effective tool in pest management, this approach is not always possible, as some materials may be damaged by exposure to low temperatures.

A FUMIGATION BUBBLE

Examination of the fire screen during the acquisition process showed evidence of insect activity, however, due to some of its components, it was not a suitable candidate for freezing. The antique glass sides of the cabinet gave us pause, as they could become embrittled in the freezer, necessitating a different solution.

Instead, we chose to fumigate the screen using a technique involving a carbon dioxide gas bubble. This process uses carbon dioxide gas to displace oxygen within a sealed enclosure, lowering the percentage of oxygen to a level sufficient to kill all stages of the insect life cycle. Air is evacuated from the bubble by creating a vacuum, then replaced with carbon dioxide. The object is left in this enclosure and monitored for approximately three weeks before being removed.

While techniques and materials used in taxidermy have changed over time, the major challenge faced in preserving this type of object remain. Taxidermied animals are irresistible to certain insects and the elaborate nature of the parlour domes and screen, encapsulating the birds in glass, make it difficult to identify insect infestation in its early stages. Vigilance through preventive conservation, followed by swift reaction to any newly perceived activity is paramount to maintaining the beauty of these objects.

REFERENCES

Farber, Paul Lawrence, “The Development of Taxidermy and the History of Ornithology,” Isis, Vol. 68, No. 4. (Dec. 1977), pp. 550-566.

Morris, P.A. “An Historical review of bird taxidermy in Britain,” Archives of Natural History, Vol. 20, No. 2 (June 1993), pp. 241-255.

Poliquin, Rachel. The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012.