An Exceptional Archival Collection

Explore the Stewart Collection of Canadian and Atlantic History and discover how documenting it involved some real detective work.

May 9, 2023

In spring 2016, when I was working as a guide-interpreter at the Stewart Museum and on the point of starting a Ph.D. in history at Université Laval in Quebec City, curator Sylvie Dauphin offered me my first historical research job: working on the project to digitize and describe the Stewart Collection of Canadian and Atlantic History (then known as the Colonial Era Collection), kept at the Stewart Museum. I accepted without hesitation, since the collection coincided both with my areas of specialization (the modern era and Atlantic history) and my research interests (the social and military history of New France).

| Discover the Stewart Collection of Canadian and Atlantic History on Online Collections |

Unknowingly, I was embarking on an adventure that would last almost six months and that would captivate me again later, in the fall of 2022.

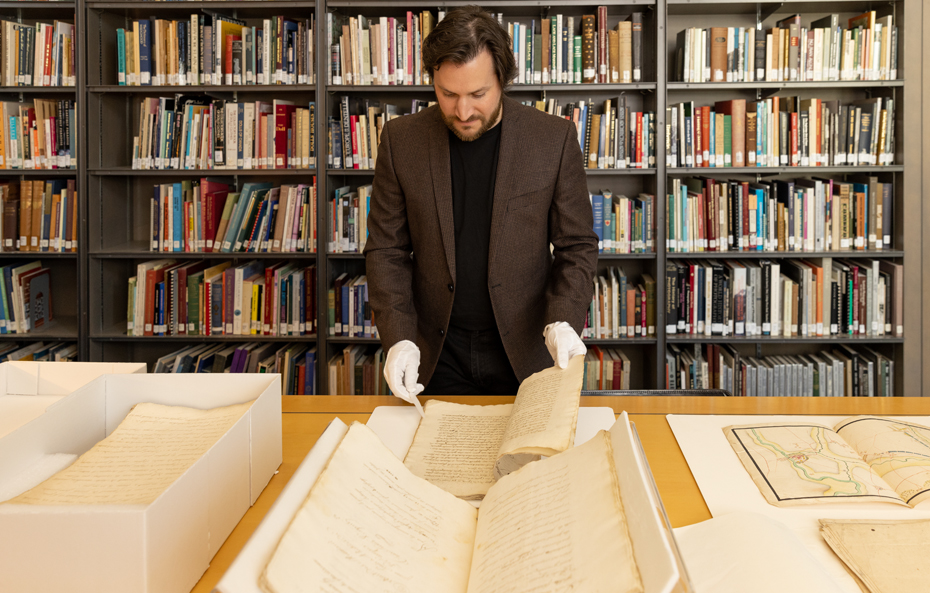

The aim of the project was to facilitate access to the collection, to help disseminate the information it embodied and to limit the manipulation of documents that were fragile and unique. My task was to write – or validate and enhance – descriptions of approximately 850 documents produced between the 15th and 19th centuries in North America and Europe. But before plunging into the research and writing, I needed to gain an overview of the archive.

THE STEWARTS' LEGACY

The collection was composed of five series assembled according to geographic area of production: France, England, Canada, United States and Other Countries. Each ensemble was divided into sub-series defined by the successive royal dynasties and political regimes of each nation. Finally, these groupings were sub-divided once again according to theme: administration, economy, military affairs, religion, civil status, etc.

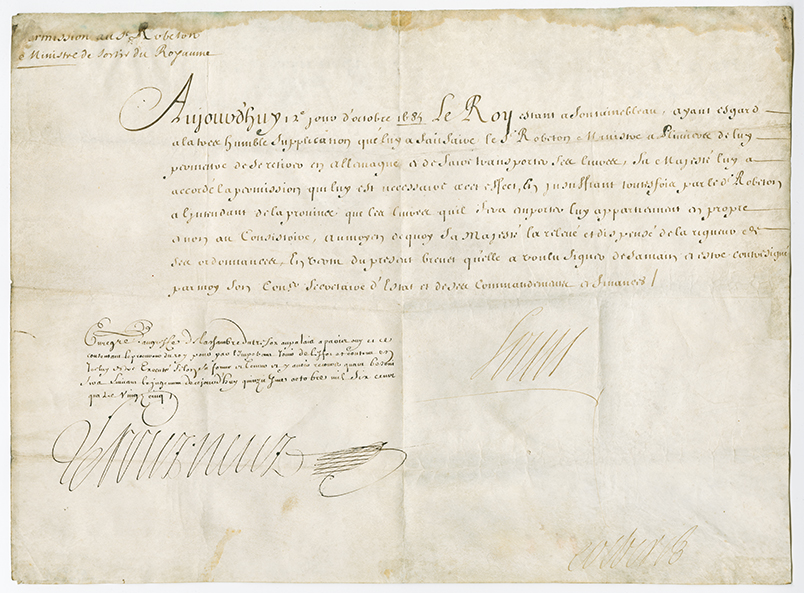

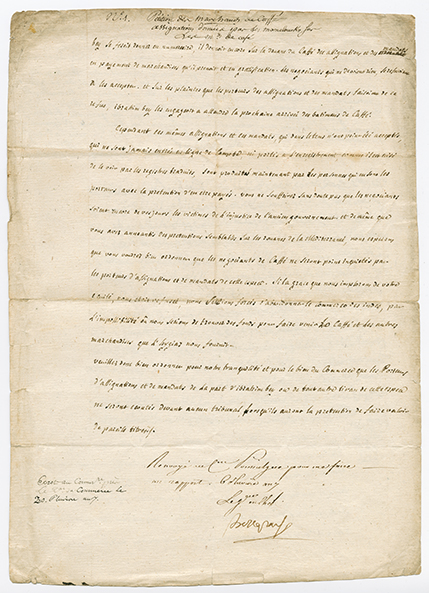

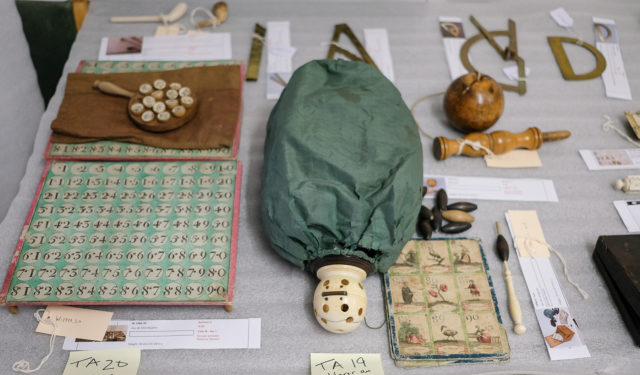

Ranging from Versailles to Louisiana, from London to Massachusetts, the collection focused essentially on the Atlantic world, and more especially on the history of France and England and their North American colonies. It contained an extremely wide variety of documents and manuscripts. They encompassed the momentous political history evoked by declarations of war and peace treaties, but also economic history, illustrated by statements of account, bills of exchange and royal ordinances aimed at the regulation of trade. Military history was abundantly exemplified by officers’ commissions, orders, discharge notices and correspondence, while social history was represented by all sorts of documents, including work and marriage contracts. Certain items, evidently selected for the historical importance of their authors, reached further afield – to Cairo, for example, for an encounter with Napoleon Bonaparte and Egypt’s coffee merchants.

Understanding the collection, which seemed at first view somewhat eclectic, required a grasp of the vision that David Macdonald Stewart (1920-1984) and his wife Liliane Stewart (1928-2014) shared concerning the teaching of the history of Canada and of the Western world. Each of the documents had been acquired through the Lake St. Louis Historical Society, founded by David M. Stewart in 1955, and every manuscript or rare book was intended to be associated with an object and an image from the Museum’s collection, to form a pedagogical whole. Now suitably enlightened, I was ready to start work. But I would be faced with a number of challenges.

A FIRST STUMBLING BLOCK: 16th-CENTURY CALLIGRAPHY

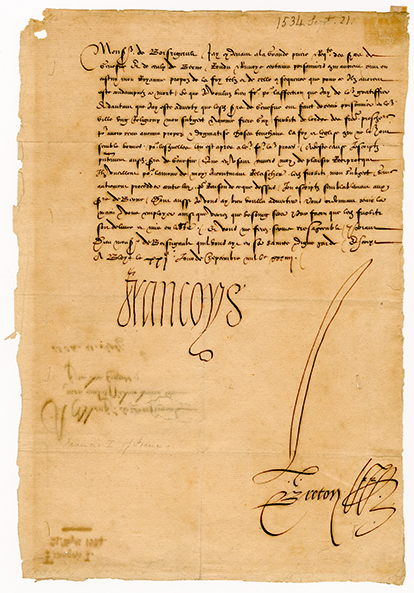

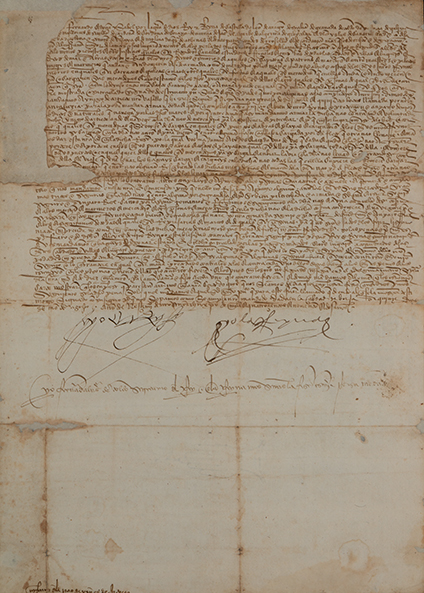

The very first piece I was required to work on, a document produced in 1534, took me immediately out of my comfort zone. It consisted of a letter (A1.1,1.1) signed by the king of France, Francis I (1494-1547), and addressed to one of his ambassadors.

Not being an expert in 16th-century paleography, I was unable to decipher the old French calligraphy. For assistance in translating several pre-17th-century documents, some written in Latin, I turned to medievalist Didier Méhu, a history professor at Université Laval. Throughout the project, in fact, I had to appeal regularly to outside experts for help in interpreting certain documents, grasping their significance and identifying their source or author. Never would I have imagined being lucky enough to one day handle a manuscript signed by Francis I, the monarch who sent Jacques Cartier on a voyage to North America in 1534. And this was just the beginning: the collection is full of documents signed by illustrious figures.

THE MYSTERIOUS MR. DE MANERÉ

I moved on to the second item. This was a compendium of draft letters (A2.1,1.1) written by an unknown author and addressed to a certain Mr. de Maneré, living in Madrid in 1718. They concerned diplomatic negotiations conducted by the kingdom of France during the Regency period (1715-1723).

Since the existing description was vague and full of gaps, I was obliged to read the entire ensemble, composed of forty folio sheets. I established a work method aimed at answering the following questions: Who was the document’s author? Where was it produced? Who was the addressee, this Mr. de Maneré? What was the sociohistorical situation surrounding it? What was its purpose? And, finally, who or what was it about?

My initial explorations into the author’s identity led nowhere. This despite the fact that the drafts were written in Paris by someone who was a frequent visitor to the Palais-Royal, seat of the Regency, and apparently close to the upper echelons of power. Nor was the recipient of the letters any easier to pin down. I found this perplexing, since whoever it was apparently exercised a role of considerable responsibility in the realm of French diplomacy.

Going over the document again, I realized that the name had been misread: the recipient was actually Mr. de Nancré. Eureka! Through further research I learned about the life of Louis-Jacques-Aimé-Théodore de Dreux, Marquis of Nancré (?-1719), who served as a diplomat in Madrid from January 1718. A protégé of Cardinal Guillaume Dubois (1656-1723), chief minister during the regency of Philippe d’Orléans (1674-1723), Nancré had been charged by the cardinal to thwart Spain’s political ambitions in the Mediterranean during a period when shifting alliances were changing the face of Europe. At last, I had (nearly) all the information I needed to complete my description and produce my first contribution to the collection’s database.

My joy was short-lived, however, when I considered that I’d just spent several days trying to understand only a single one of the over eight hundred documents contained in the collection. I was a little panicked: if there were many more similarly complex documents, I’d never be able to meet the deadline! But to my great relief, I quickly realized that most of the items wouldn’t take anything like as long to decipher, either because they were self-explanatory or because I was more familiar with the historical context.

MILITARY HISTORY AND FAMOUS PEOPLE

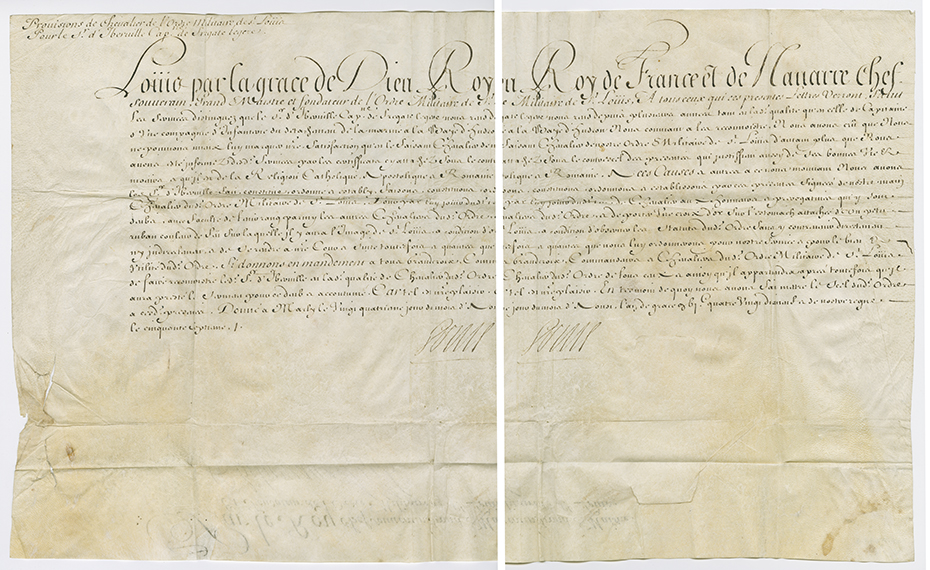

A large part of the collection is devoted to the military history of the modern era. As a specialist in the socio-military history of New France, it was a real pleasure for me to document the items in this category. I was particularly astonished to learn that we had a copy of the letters (C1.3.7) from 1699 awarding the title of knight in the Military Order of Saint-Louis to Montrealer Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville et d’Ardillières (1661-1706), the most celebrated privateer in the history of New France. Iberville, a complex but fascinating historical figure, was the first Canadian to earn membership in this order created in 1693 by Louis XIV, whose name appears at the bottom of the documents.

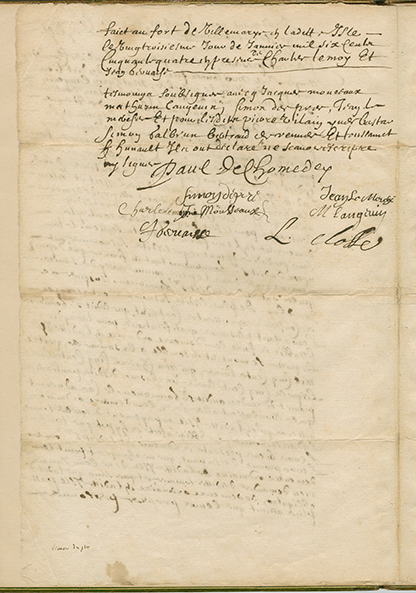

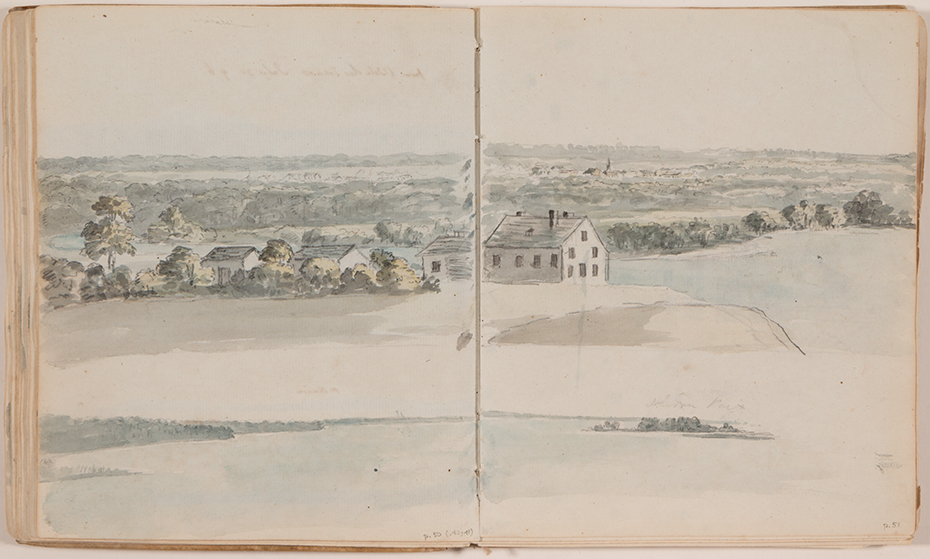

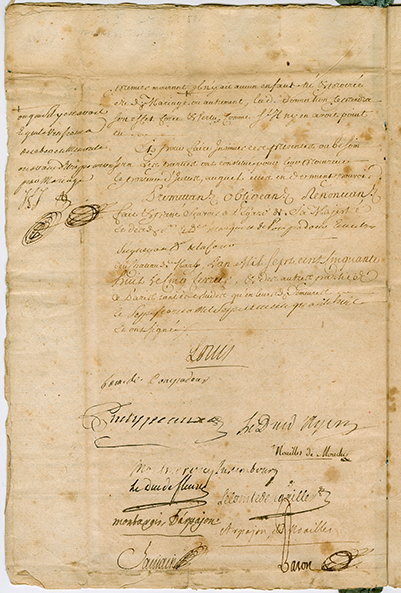

Many items in the collection are signed by major historical figures. They include queens, like Isabella of Castile (1451-1504) (E4.3,1.1), founders, like Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve (1612-1676) (C1.7,1.1), artists, like Elizabeth Posthuma Gwillim (1762-1850) (C3.8,3.2), influential courtesans, like Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, Marquise of Pompadour and Duchess of Menars (1721-1764) (A2.5,3.2) – and also characters who need no introduction, like Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) (E3.2,1.1). Part of the collection’s significance and prestige resides in the direct contact it offers to individuals who have shaped history.

A COLLECTION FOCUSED ON HISTORICAL TURNING-POINTS

The interest of the collection goes beyond its illustrious signatures, however, for the documents it contains shed light on a number of pivotal moments in history. These include the early years of Montreal’s foundation, alliances reached between French incomers and Indigenous people, the wars that took place on North American soil, the French and American revolutions, the Patriote rebellions, the Industrial Revolution, and the religious wars that so bitterly divided Europe from the 16th to the 18th centuries. As I delved, I discovered new historical subjects and learned of little-known events.

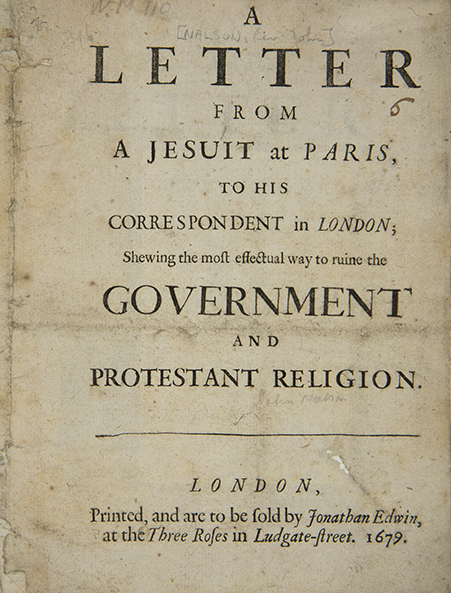

For example, the section devoted to England contains several Protestant pamphlets dating from the late 1670s that were aimed at discrediting the country’s Catholics. They were produced as part of the anti-Catholic frenzy that swept through the kingdom as a result of the so-called Popish Plot – an entirely fictitious conspiracy, concocted by an Anglican clergyman, alleging that Catholics were planning to overthrow the monarchy. Clearly, fake news is nothing new!

A MYSTERY SOLVED

My task proved both intellectually stimulating and professionally instructive. I made the acquaintance of diligent individuals who supported me throughout my endeavour, and I had the opportunity and privilege of being able to manipulate and study extremely rare documents. When, in the fall of 2022, the Museum’s Curator of Archives Mathieu Lapointe approached me to undertake the final revision of the descriptions and their translations, I accepted immediately. Since then, we – the team includes archivists Patricia Prost and Anouk Palvadeau – have been working on the final phase of the collection’s online launch. It’s been a thrill to have the chance to immerse myself in these archives once again.

Only at this stage, years after my first contact with the collection, has further research finally enabled me to identify with almost complete certainty the author of the letters addressed to the Marquis of Nancré, the initial document that caused me such headaches. It was Charles Mordaunt, 3rd Earl of Peterborough and 1st Earl of Monmouth (1658-1735), an English diplomat who lived for a time in Paris in the home of the marquis’s mother. It was she who served as go-between for the diplomatic intrigues devised by the Earl of Peterborough and the Marquis of Nancré.1

I could say a lot more about the challenges I encountered and the gems I unearthed during my research, but I’ll stop here and leave you the pleasure of exploring this precious archive, now entirely accessible online. It’s your turn to fall under the spell of these historical treasures!

NOTES

1. Émile Bourgeois, La diplomatie secrète au XVIIIe siècle, ses débuts. I. Le Secret du Régent et la politique de l’abbé Dubois (Triple et Quadruple alliance (1716-1718) (Paris : Colin, 1909), p. 325.