Dr. Fenwick’s Patients

Not to Be Sold: Privacy at Notman’s Studio or Controlling One’s Image in the 19th Century (Part 6 of 6).

June 28, 2022

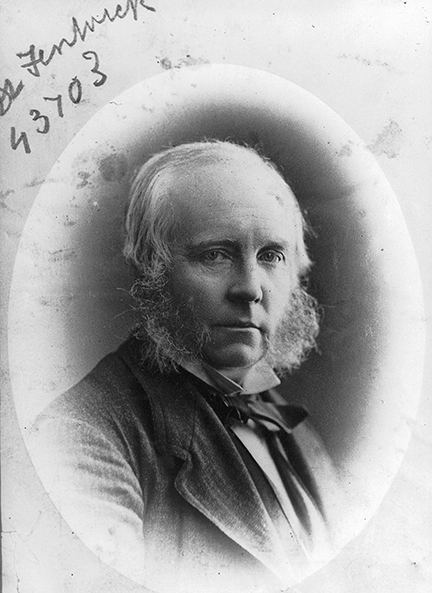

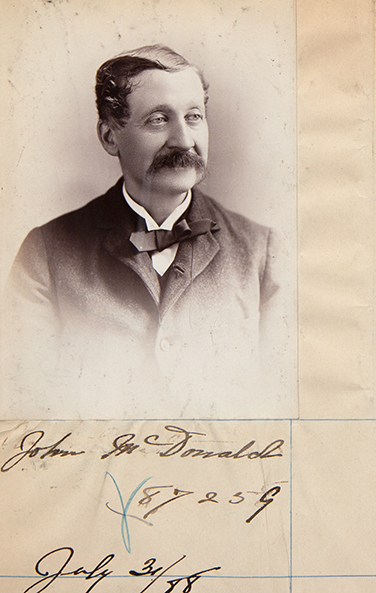

Privacy is at stake in the photographs of patients for Dr. George Fenwick, professor of surgery at McGill University in Montreal from 1875 to 1890. During this period, Fenwick collected specimens for the university’s medical museums and took an interest in innovative procedures and protocols. For example, in the 1870s he developed a new knee surgery that reduced the need for life-threatening leg amputations and instituted new antiseptic methods at the Montreal General Hospital.

MODERN APPROACH

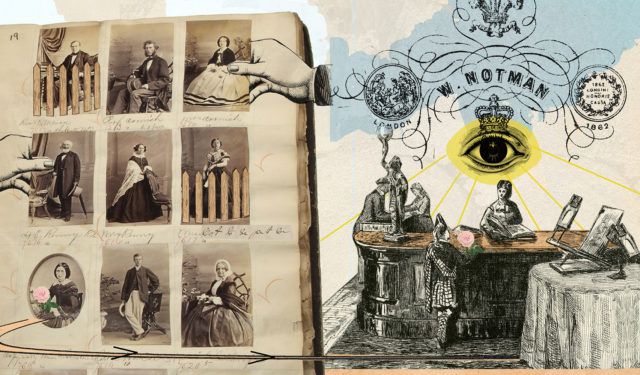

Fenwick’s embrace of photographic technology logically follows his modern approach to medicine and his interest in teaching from visual aids. Over the course of his tenure at McGill, Dr. Fenwick regularly had his patients photographed at Notman’s.

| You missed the beginning of this series? Here is the first article Welcome to the Studio |

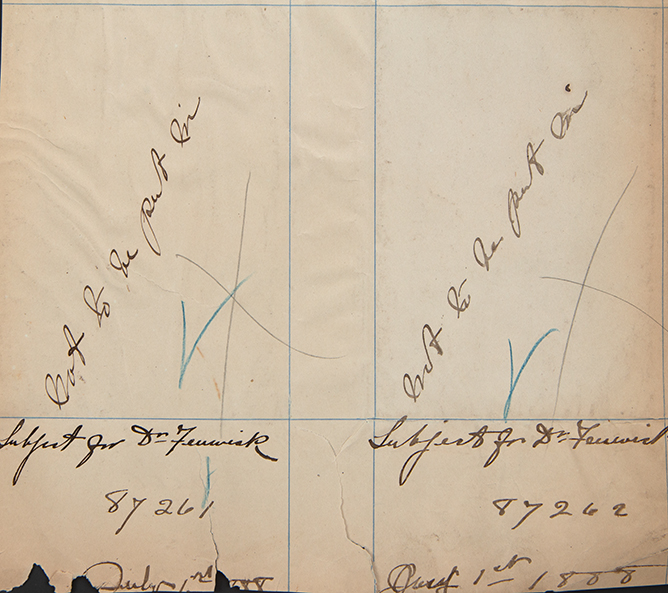

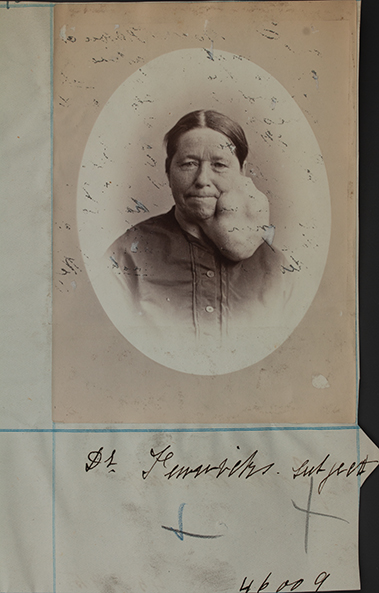

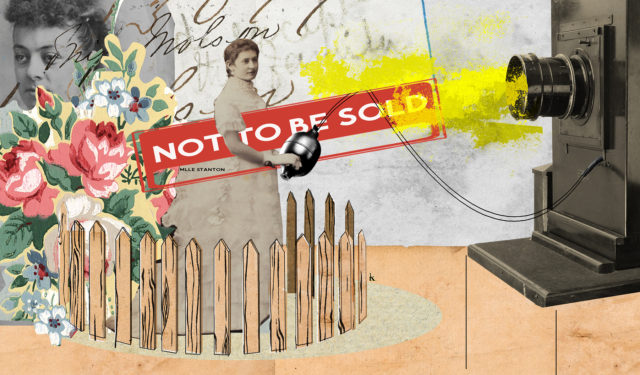

Notman did not register the names of most patients photographed in this collaboration. A few of the Fenwick photographs included the restriction that prints were “not to be put in” the Picture Book, and the negatives for these restricted images are also missing from the archive. However, there was no standard application of privacy applied to clinical portraits made in the Notman Studio.

In 1877, Fenwick sent a female patient with a goitre on her neck to Notman’s studio to have her malady documented. She returned after undergoing a successful surgery to remove the growth. Both photographs appeared in the Picture Book and no restriction seems to have been placed on these images, by either Fenwick or the sitter.

VICTORIAN MODESTY

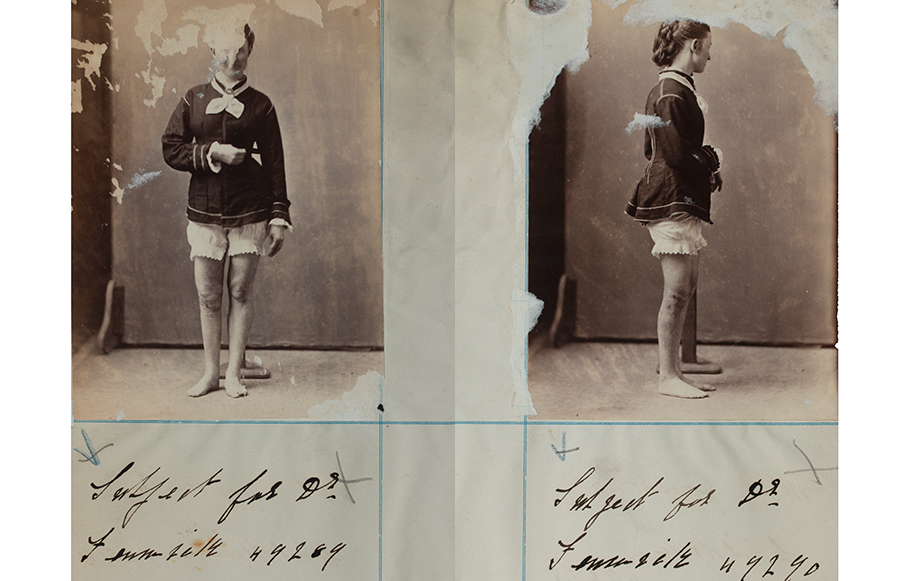

In 1878, Notman or one of his staff photographers photographed a female patient with a mild malformation of the leg, possibly related to Fenwick’s research on leg surgeries. There do not seem to have been any restrictions placed on the images’ inclusion in the studio’s Picture Books nor on their sale, but it may have been understood that subjects for Dr. Fenwick were only for his use. Nonetheless, when the McCord Museum’s archivists found these portraits in the Picture Book, they were hidden under pieces of paper. Evidently, someone in Notman’s studio pasted flaps of paper over the patient’s images, a rare intervention seen only in the case of clinical photographs in the Picture Books.

Given that no one exerted any censorship over the image of the patient with the goitre, it seems that the restriction applied to the images of the woman with a misshapen knee is unlikely to be traced to the unsightliness of her medical condition. After all, Victorians flocked to displays of physical oddities, as evidenced by the vast popularity of exhibitions of human curiosities such as P.T. Barnum’s American Museum.

In the context of Victorian modesty, it was risqué for women to expose even an ankle, let alone pose in nothing more than bloomers below the waist. The pasted paper points to the potential for Notman’s staff to exert another level of control and restriction over the images by determining the measure of privacy afforded to clinical portraits or the degree of protection Notman’s staff members should have from the sometimes-startling photographs.

NO NEED FOR EMBELLISHMENT

The clinical portraits taken for Fenwick by the Notman Studio differ from comparable collections of early medical and prison photography, which tend to show subjects who are clearly struggling to resist having their likenesses captured. Notman’s subjects seem relatively comfortable in front of the camera. That being said, Fenwick’s patients were not afforded the same comforts that were customary for Notman’s regular clients.

Whereas a commercial portrait was typically set against a luxurious backdrop that included furniture, carpets, and other props, Fenwick’s patients are positioned in plain, simple spaces. These are utilitarian medical images and there is no need for embellishment.

Whatever their origin, the restrictions placed on some of these images might be seen to demonstrate an early concern for the dignity of patients; however, the fact that many of these images were permitted to appear in the Picture Books suggests that Fenwick and Notman’s interest in the patients themselves was selective.

NEW NORMS

Not long after these photographs were taken, most medical photography shifted out of the commercial studio and into the doctor’s office with the help of handheld cameras. The notable lack of agency afforded to these sitters provides an indication as to why patients began to demand more control over how their photos were used by physicians at the end of the 19th century, leading to legal disputes over consent and privacy that created new norms for patient care.

Today, new questions regarding photography and patient privacy have emerged as an increasing number of medical practitioners, particularly dermatologists and plastic surgeons, have found success on social media platforms like Instagram, where they post images and videos of ailments and treatments to generate interest in their services.

The series Not to Be Sold: Privacy at Notman’s Studio is supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.