Archival Memories

Discover the realities and challenges facing archivists, whose work is essential to preserving our collective memory.

June 7, 2021

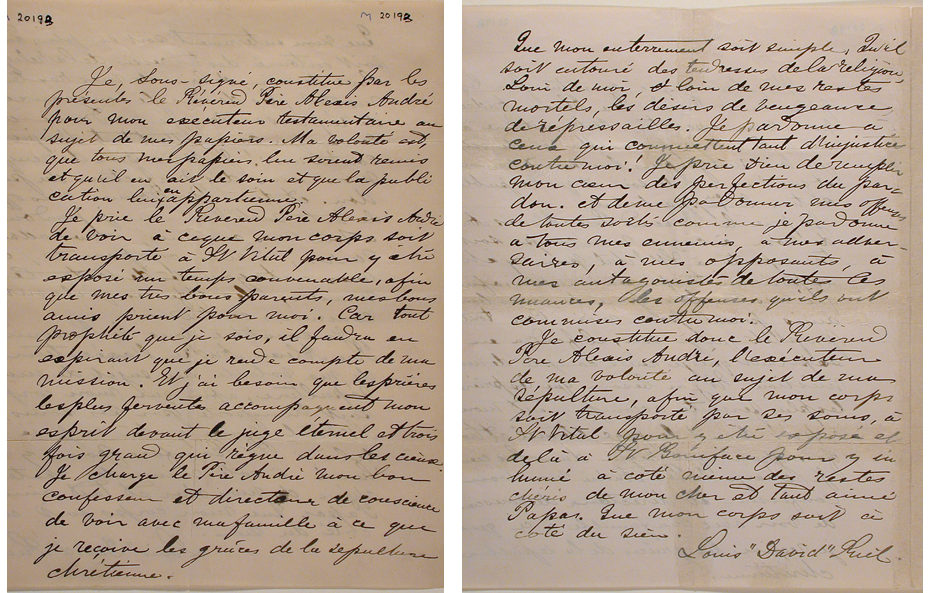

Put it in the archives. Your file will be archived. It is funny how, in everyday life, the verb ‘archive’ seems to mean the same thing as shelve, or remove from sight. Suddenly, the thing in question is outdated, no longer relevant to the present and likely to be forgotten. However, far from being a place where documents go to disappear, archives are in fact a form of collective memory. The act of archiving involves organizing an eclectic collection of memories so our history can be reconstructed.

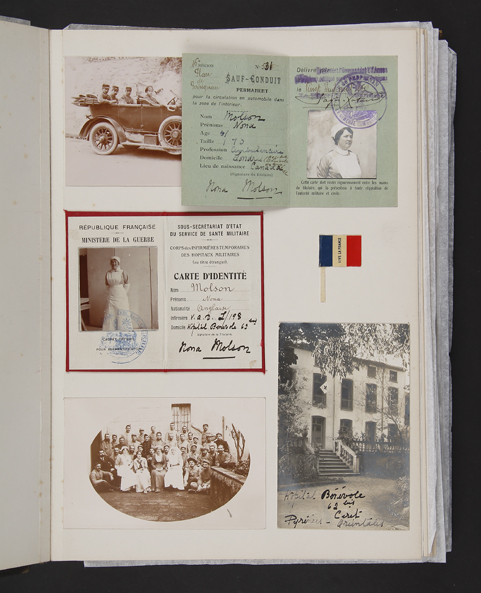

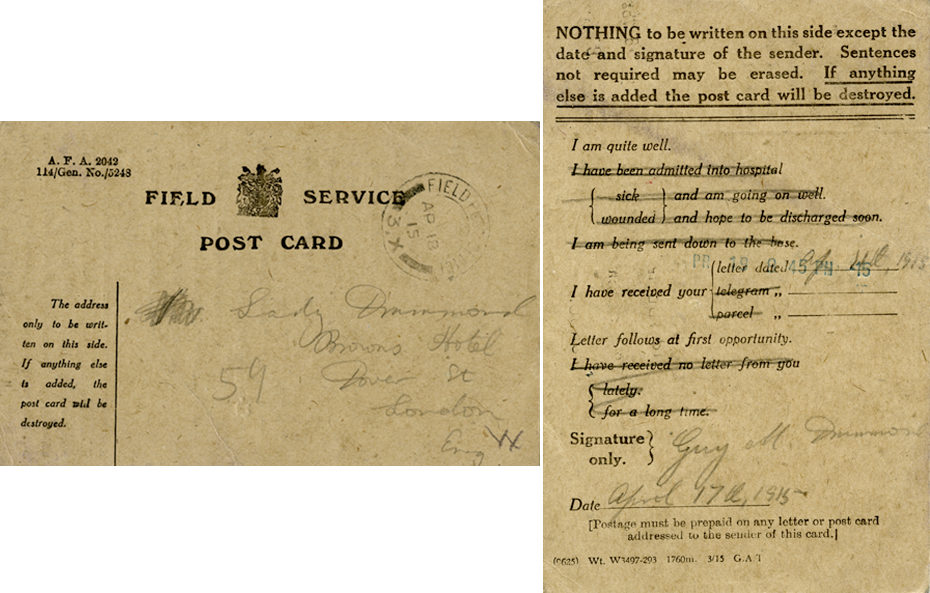

In anticipation of International Archives Day, I sat down with Philippe-Olivier Boulay-Scott, an archivist who has worked on several of the McCord Museum’s archival fonds. I feel really fortunate to be able to work in the field of history, he says with a smile. My first big mandate at the Museum was to work on the Drummond Family Fonds, which presented a number of special challenges. Since it is a family fonds, the documents were produced by many different people. It’s very complicated to describe it properly because there is so much information to verify.

THE ARCHIVIST'S WORK

The archivist’s job is to preserve, disseminate and bring documents to life, explains Philippe-Olivier. Conserving documents involves maintaining their physical integrity, documenting them and sometimes digitizing them. The work therefore includes both repetitive manual tasks and intellectual labour.

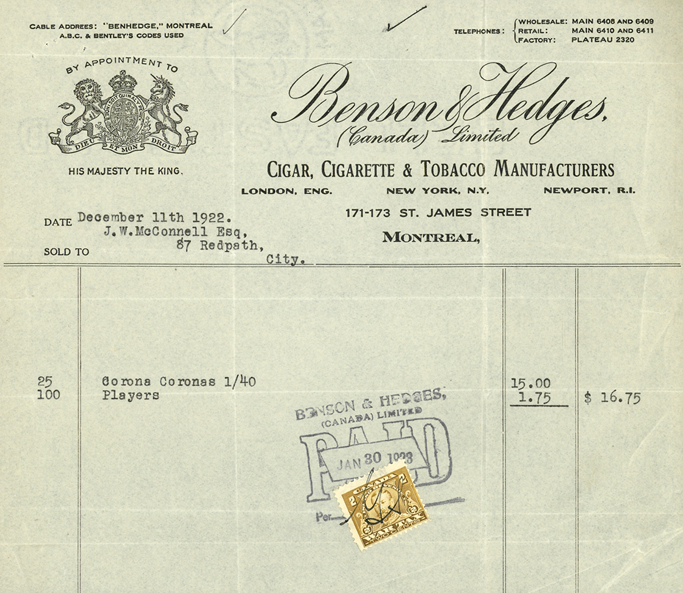

Moreover, his job does not entail archiving every scrap of paper that comes his way. Especially in the case of everyday archives like receipts, grocery lists and administrative documents, there are so many it is important to decide what is worth keeping and what can be discarded.

Philippe-Olivier notes that it is critical to push back against any potential biases that could exacerbate the marginalization of people in our archives. I know that the Museum is increasingly focussed on promoting a more inclusive view of our social history and I am very happy about that.

THE ROLE OF DIGITIZATION IN THE INFORMATION AGE

The problem today is that there are so many documents, it is hard to know where to begin, he confides. Given the explosion of information in the digital age, it is currently impossible to digitize all archives. Furthermore, it is dangerous to believe that everything can be found online, because this can create the impression that whatever is not there does not exist. On the contrary, remarks Philippe-Olivier, only 2% of BAnQ’s collection is online. Instead, digitization is a way of showcasing a limited number of special documents. Archives must be kept alive through use, he laughs.

INTERNATIONAL ARCHIVES DAY

A day celebrating archives is really an opportunity to raise awareness of what we do, why we do it, and how people can participate, says Philippe-Olivier, lamenting that archives are important, but misunderstood. As you take notes during this interview, you are creating an archival document. Archives are essentially composed of information recorded on a medium, which covers quite a broad spectrum. Even a tombstone is an archive! In other words, archivists work to preserve information produced by people, both written and audiovisual, stored in an analog or digital medium.

Unfortunately, adds Philippe-Olivier, the resources earmarked for archives are negligible. Many archives centres, those outside metropolitan areas for example, are underfunded. However, archives are necessary for writing the history of tomorrow.

What we keep will determine what historians will be able to study in the future.

What do we want future generations to know about our history? More importantly, who will have the privilege of being represented in history and who will be missing?

To address this issue, a number of community archives, like the Quebec Gay Archives, have been founded in Quebec, but many aspects of our society and our history are still in danger of being forgotten. Our social interactions are increasingly online, posing a major challenge to archivists: just think of all the information recorded in our digital devices, from Facebook posts and YouTube videos, to tweets from public figures and blogs. This type of content often disappears as quickly as it is produced. There are many things—entire subcultures—with an Internet presence, , worries Philippe-Olivier.

The archivist’s effort to preserve memories is a never-ending, recurring task, and every archives centre, be it BAnQ, the McCord or a more modest organization, is a guardian of collective memory, guaranteeing that our joys, our worries, our social and administrative communications, in short, our lives, will resonate in the future. Across Quebec, thousands of archivists like Philippe-Olivier endeavour to maintain our memories so that as many people as possible can confidently say, Je me souviens—I remember.