The Tranquility of the Countryside Versus the Hubbub of the City

As the Museum’s archives attest, city and country have been radically opposed in the minds of Quebec’s inhabitants for the past two centuries.

June 6, 2025

An exploration of the various historical archives held by the McCord Stewart Museum reveals that the tension between town and country has long existed in Quebec, reflecting attitudes that are still very much alive today.

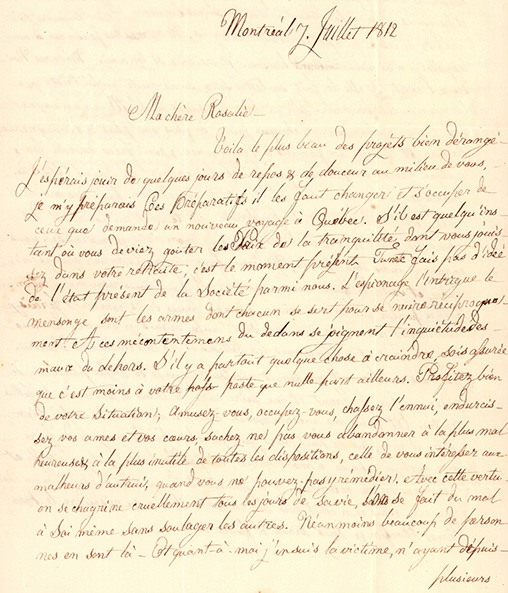

The contrast between the stressful and hazardous bustle of urban life and the soothing calm of the country was already being evoked in the early 19th century, in the writings of politician Louis-Joseph Papineau (1786-1871). Caught up in the tumult of the business deals, intrigue and political struggles that characterized Montreal, he wrote on more than one occasion to his sister Marie-Rosalie (1788-1857) about how he envied her quiet life in the country, at the family seigneury of Petite-Nation, in the Outaouais:

“How often in the midst of all this brouhaha have we wished to be sharing the comfort of your retreat, have we pondered your good fortune. I must compliment you on the advantages you seem to have derived from your solitude. I do not congratulate you for the maturity of reason, the stoical strength, the philosophical courage with which you endure your exile. I would wish to be there, and would be happy, and would be as wise as you, poor wretch that I am.”

December 9, 1811

“I was hoping for a few days of rest and comfort among you, and was preparing for it. I must alter these preparations and busy myself with those required for another trip to Quebec City. If there is any moment when you should savour the peace and tranquility you enjoy in your retreat, it is now. You have no idea of the present state of society among us. Spying, intrigue and lies are the weapons everyone employs to harm one another, and to these annoyances from within must be added the worry of evils from without. Although there are things to be feared everywhere, rest assured that it is less true of your place than anywhere else. Make the most of your situation …”

July 7, 1812

The Unsanitary City

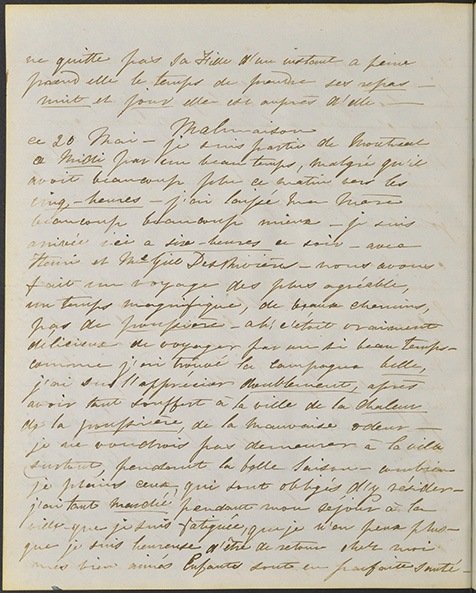

Busy and chaotic, the city was also perceived as extremely dirty and unsanitary, since the development of its urban infrastructures had failed to keep pace with the needs of a rapidly growing population. For Marie-Angélique Hay Des Rivières (1805-1875), a resident of the Eastern Townships who was visiting Montreal, the city’s insalubrity and pollution were particularly evident in early summer. On May 19, 1848, she wrote in her diary: “It’s unbearably hot, and so dusty you can hardly see – I’ve never experienced anything like it in my life.”

On May 20, after leaving the city, she noted: “How beautiful I found the country, I appreciated it all the more having suffered so in town from the heat, the dust and the bad smell. I wouldn’t care to live in the city, especially during summer.”

This image would endure. According to historian Caroline Aubin-Des Roches, at the turn of the 20th century “the metropolis was seen as a suffocating place where the heat was sweltering, people were crowded together and daily life moved at an alarming rate. With the constant noise and dust, it was a world that during summer heatwaves seemed practically unlivable.”

The Unsafe City

The intense industrialization and urbanization of the second half of the 19th century brought many challenges to Montreal, which had become Canada’s most populous city and its largest industrial centre. As the population burgeoned, increasing security problems arose, owing in part to what many considered an inadequate and inefficient police service.

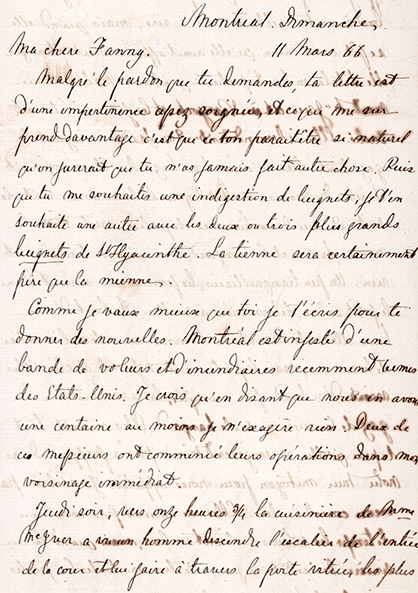

In a letter to Fanny Leman (1844-1914) dated March 11, 1866, Louis-Antoine Dessaulles (1818-1895) described how his neighbourhood had been plagued by robberies:

Montreal has been overrun by a gang of thieves and arsonists recently arrived from the United States. I don’t think I’m exaggerating when I say there must be a hundred, at least. Two of these gentlemen have begun operating in my immediate neighbourhood … The bandits invariably choose a time when all the men are absent. You can imagine how upset everyone is. The police service is entirely inadequate for the city, and everyone is more or less obliged to protect themselves.

The Countryside: A Restorative Haven, with None of the City’s Drawbacks

Aside from the perceived discomforts and dangers of the city, the frenetic pace of urban life contrasted sharply in many minds with the tranquility of rural living. Caroline Aubin-Des Roches explains that industrialization, urbanization and technological innovation “created the impression that the world had become more complex and that time had accelerated.”

This notion seems to have already occurred to Marie-Angélique Hay Des Rivières, who was unable to imagine living in Montreal: “How I pity those obliged to reside there. I walked so much during my stay in town that I’m exhausted, I’ve had quite enough, and I’m happy to be back home.” (May 20, 1848) This despite the fact that she complained on her return about the hordes of mosquitoes surrounding her house in the country!

Later, the image of a city in perpetual motion would continue to be compared to the calm of the country –increasingly so with the development in the early 20th century of the Scout and Guide movement. The city-country divide is evoked in the Guide camp notebook of the 47th Company from Lachine, from 1963, which is part of the Murielle Mailloux (1942-) fonds.

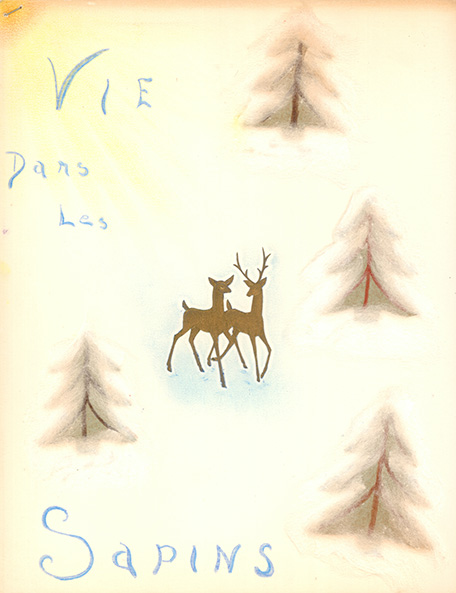

The notebook elaborates on the camp’s theme – “Life among the Fir Trees” – in the following passage:

From the calm of a winter landscape, when a golden mist envelops blue mountains whose patches of mauve snow and resinous evergreen trunks glimmer with frost, there emanates an impression of peace, of purity, of profundity, of so many things of which we have need… The hectic rhythm of city life fades away, engulfed in the splendour of a Laurentian landscape. The life concealed behind this rampart of firs, once discovered, keeps us constantly in a zone of calm that allows us to strengthen and express our mission as Guides.

As historian Pierre Savard explains in his article “L’implantation du scoutisme au Canada français,” the Scout movement took root in Quebec during the 1920s as “an at least partial response to the lack of organized summer activities for children in a city like Montreal,” while also providing a context for teaching Christian values. The subject was discussed in an article by editorialist Omer Héroux (1876-1963), published in Le Devoir on March 6, 1926, where he stressed the benefits of rural life – a source of development and happiness less easily accessible to young people from urban areas:

We are once again confronted here by one of the many problems resulting from the existence and growth of large cities … We ask all those city-dwelling children fortunate enough to have spent their holidays with family in the country to cast their minds back: when were they ever happier? At the same time, children develop physically and learn. Rural life is a great school for initiative, resourcefulness, problem-solving and energy. In town, the situation is quite different. Once school is over, thousands of young children find themselves out on the street with nothing to do.

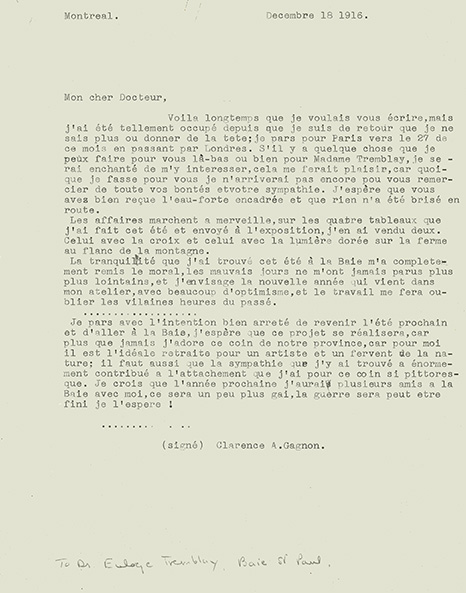

The countryside also proved to be a particularly effective source of rejuvenation for artists, as witness a letter dated December 18, 1916, from the painter Clarence A. Gagnon (1881-1942) to Dr. Euloge Tremblay (1878-1946). After a summer art sojourn in the Charlevoix region, Gagnon described how positive he had been feeling since his return:

The peace I discovered this summer in Baie-Saint-Paul completely restored my morale, the dark days have never seemed more distant, and I look forward to the coming new year in my studio with much optimism, and work will make me forget the dreadful times of the past.

He went on to enthuse about Baie-Saint-Paul and its inhabitants: “I love this part of our province, since for me it offers the ideal retreat for an artist and a nature lover; it must also be said that the sympathy I encountered there has contributed enormously to my affection for this picturesque region.”

For the past two centuries, then, the idealization of the countryside and nature has traversed the history of Quebec, taking various forms and manifesting itself today in contemporary culture. Often, though, it seems to be both the reflection and the reaction of a society that is, more than ever, irrevocably urban.

To learn more

- To learn more on the Shared Emotions project

- To learn more on the Textual Archives Collection

- To learn more on the Des Rivières and Taschereau Families Fonds P752

- To learn more on the Murielle Mailloux Fonds P687

- To learn more on the Clarence A. Gagnon Fonds P116

- To learn more on the Dessaulles, Papineau, Leman and Béique Families Fonds P010

References

Aubin-Des Roches, Caroline. “Retrouver la ville à la campagne : la villégiature à Montréal au tournant du XXe siècle.“ Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine, vol. 34, no. 2, 2006, pp. 17-29. https://doi.org/10.7202/1016010ar

Héroux, Omer. “Pour nos enfants.” Le Devoir, March 6, 1926, https://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/2802880

Savard, Pierre. “L’implantation du scoutisme au Canada français.” Les Cahiers des dix, no. 43, 1983, pp. 207-262. https://doi.org/10.7202/1015550ar

Thank you

This project has been made possible in part by the financial support of Library and Archives Canada.